Two decades ago, Laura Vinroot Poole told a close friend that she was expecting a child. The reply still makes her wince: “So are you going to close the store?”

That store, Capitol, had grown into one of the most celebrated luxury boutiques in the country, and Poole was a budding star in the fashion business, piercing the notoriously cutthroat industry with her taste and kindness, a rare angel in a world of devils wearing Prada.

“No, I’m actually not,” Poole, then in her early 30s, told her friend. “I’m going to figure out how to do this and raise a hopefully happy, healthy child who doesn’t hate me. But I also want to show her what it means to have meaningful work.”

Last month, Laura and her husband, Perry, dropped that daughter off at college in Tennessee. A few days after that, Poole jumped on a plane to Belgium to scout and buy Dries Van Noten clothes for her shop, Capitol.

Now in its 28th year of operations and located in SouthPark, Capitol is a bellwether boutique for American fashion, which in some ways makes it a bellwether of the American mood. A stroll through the store these days takes you past racks of classic looks and earthy colors and floral dresses — a subtle reflection, perhaps, of a desire to cling to peace and nature amid turmoil and uncertainty.

Poole defaults to steadiness. She makes eye contact, remembers names, and moves with a gentle purposefulness. She also owns Poole Shop, for more relaxed looks, on the second story of Capitol. And she has a men’s store down the street, Tabor, along with a second Capitol location in Los Angeles. She’s been featured in Vogue and Garden & Gun and all sorts of national magazines. Movie stars and CEOs find their way in, but the shop runs on regular customers. Capitol is internationally recognized as one of the best shops anywhere for curation and service.

So no, she didn’t close.

But she’ll tell you her work is never only about clothes. Capitol is a kind of civic stage, where clients become friends and where women build careers. She has about 30 employees overall, most of whom are women, and Poole sees her role as helping them balance families and the many life changes that come with womanhood. She is a breast cancer survivor herself. She and Perry have raised “the coolest” daughter, she says. She’s endured through a recession that nearly ended the store. And, just last year, she delivered the eulogy at her mother’s funeral.

She’s created a work environment to help her employees navigate any such life event. They work flexible hours to make daycare and school pickups. Some are getting married; others have been through divorces. Some have worked here for nearly 20 years. One employee recently had heart surgery, and the surgeons happened to be two of the employee’s most reliable clients.

“I wanted to enable them to look at it as a lifetime career, not just a temporary job until somebody ‘rescued’ you,” she tells me. “I wanted them to have independence and control over their lives. I think we all crave for that our whole life.”

Until this summer, I only knew Poole through words and photos in glossy magazines. I’d heard about the star-studded 20th anniversary party she threw on a farm for Capitol in 2018, with a guest list that included former Vogue editor-at-large André Leon Talley and Mad Men actress January Jones.

What, I wondered, could a person like me, who typically wears whatever sales-rack clothes he purchases straight out of the store, possibly have to talk about with a fashion maven? Then a mutual friend, Sarah Olin, told me over lunch this summer that Poole’s story isn’t about clothes, but one of “beautiful leadership.”

When I walked into Capitol for the first time, I’m certain I looked lost. But Poole greeted me with a soothing smile and held out her hand. “I’m Laura,” she said through a soft old-Charlotte drawl, and I swear it seemed like a calming breeze had blown across the continent. Here was one of the world’s most famous fashion minds, friend to Hollywood stars and Charlotte’s most influential women, the very best at what she does. And she was impossibly earthbound.

She’s an antidote to many of the conversations we see elevated in Charlotte and the country today, of conflict and violence and destruction. She brings light into the room.

Over the course of multiple conversations with her and people who know her, I’ve come to understand how she’s preserved her status and humility, and how she deploys both in service of future generations.

Capitol is a distinctly Charlotte story, and Poole is a proud Charlotte native. She regularly recites the famous 125-year-old quote from the late Charlotte author and cultural force Mary Oates Spratt Van Landingham, who said that North Carolina is a “vale of humility between two mountains of conceit.”

Above all, she’s an extension of the woman who most shaped her: her mother, Judy Vinroot, the former first lady of Charlotte.

Shift the setting, and head up to the 23rd story of an uptown skyscraper, into the law offices of Robinson Bradshaw.

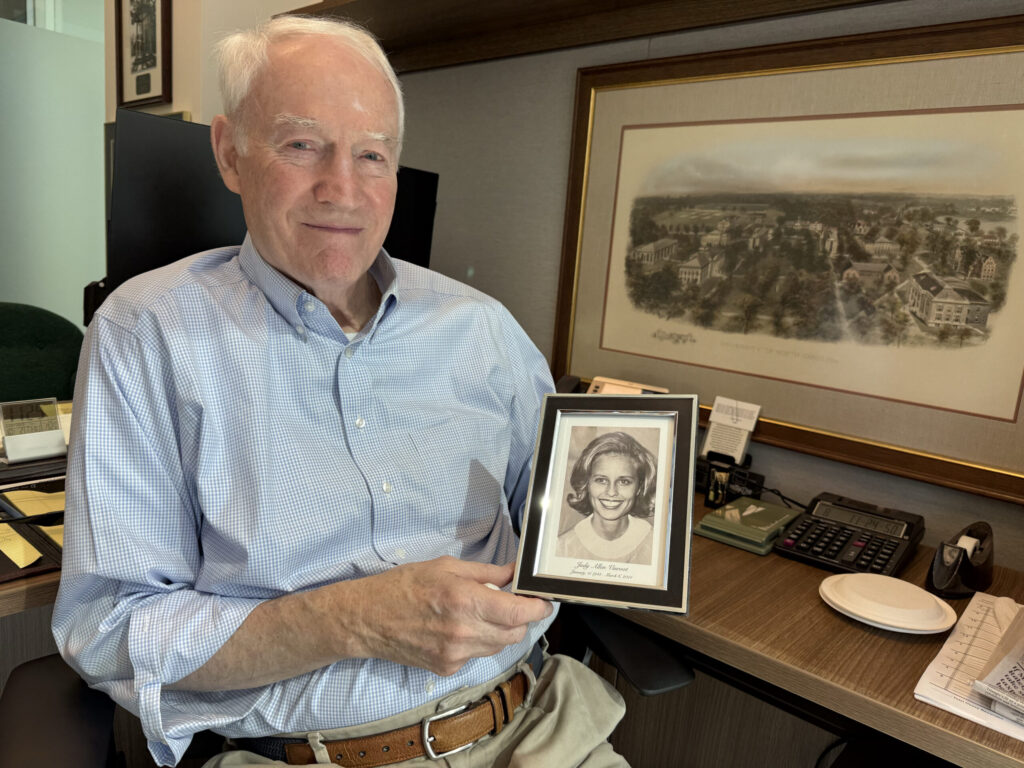

Richard Vinroot is 6-foot-8, a longtime lawyer here, a former UNC basketball player, former two-term mayor of Charlotte, former Republican nominee for governor. He’s a powerful figure still, at 84 years old. But he’s cried every day since March 6, 2024, when his wife of 59 years died after a long bout with cancer.

During our meeting last Thursday in his office, I posed a simple question — how has his daughter remained grounded despite her success? — and he broke down.

“She’s her mom,” Richard said, chin trembling. “She was just great. Judy was just a kind, k-, k-, kind person, a lovely person.”

“I’ve cried every day for a year and a half,” he went on. “I just adored her.”

If Capitol feels different from other fashion houses, it’s because Laura built it in her mother’s image, as a place where ambition and elegance don’t cancel out kindness but reinforce it.

Judy Allen was a class officer and cheerleader at UNC-Chapel Hill when Richard courted her. He was smitten at first sight; she needed convincing. She was a liberal; he was a conservative. She was 5-foot-3; he was a foot and a half taller. It worked.

He served in Vietnam, and they settled in Charlotte, his hometown, and got involved in civic life. She taught first grade in CMS and adult literacy at CPCC. She also taught Sunday School for children with disabilities at Myers Park Presbyterian Church, and was a longtime board member at The Salvation Army. He was an attorney and became a city council member and Charlotte’s mayor from 1991 to 1995. Then he ran unsuccessfully for governor three times.

Judy traveled all over the state with him for those campaigns, even though she disagreed with his positions. It’s almost hard to fathom through the rearview mirror of today’s politics, a love like theirs across political differences.

“I would always joke with her: ‘You be sure to vote Wednesday,’” Richard said. “And she’d say, ‘Richard, I know the election’s Tuesday. I’ll be voting on Tuesday.’”

They had three children, Laura in the middle. She was brilliant, but always an “iconoclast,” Richard says, challenging his more rigid thinking. She finished high school at Andover in the northeast, then went to UNC. She dropped out after a year and moved to the southwest, where she showered “three times in three months,” and explored a hippie life. She then came back to North Carolina and worked with crafts at Penland before returning to UNC and completing an arts degree.

Her father was crushed when she dropped out. He barely talked to her for a year. But Judy “understood fully,” Richard says. “She was so much smarter than me. … I saw things black and white, and Judy saw gray.”

Laura saw colors everywhere. She was a “Deadhead,” she says. She loved thrifting. But she’d also grown up helping her mom’s friends dress for galas. She was working for a store in Raleigh in the 1990s when she met Perry Poole, who had dreams of being an architect. She also helped on her dad’s campaigns for governor, traveling around the state.

It was at a campaign stop in Wilmington where Laura told her father that she and Perry had eloped. Richard drove all the way across the state with a lump he couldn’t swallow, but when he got home, “Judy, of course, she already knew it. And she was fine with it,” he says. “I was sort of a martinet, and Judy was just the opposite. She was far more flexible, understanding that she was a soulmate of all three of them.”

Laura’s more forgiving.

“I have tested him,” she says with a grin. They still eat dinner together every Sunday night.

When Judy died last year, Richard could barely walk in the building for the memorial service. Laura stood up and told the crowd about her mom.

“My dad was, like, the sun,” Laura told me of her childhood. “You don’t realize how much all of our lives reflected him, because he is this giant 6-foot-8 creature, and very high standards. … But I think [after Mom died] we all of a sudden realized maybe it wasn’t Dad that our life revolved around. Maybe it really was Mom.”

Laura is, like anyone, a blend of all her influences. Yes, she’s known as one of the nicest people in the fashion industry, and that certainly comes from Judy.

On one of our walks through Capitol recently, though, she discreetly grabbed a long dress off a rack and asked a staffer to take it off the floor, as if she didn’t want me to notice. I asked her what that was about, and she said the dress was wrinkled and shouldn’t have been on display. For a hippie/artist/Deadhead, she’s got pretty high standards, too.

“I didn’t just want to have the best store in Charlotte,” she’s told me a couple of times. “I’ve always wanted to have the best store in the country.”

Capitol sells beautiful things that are out of reach for many. Poole doesn’t pretend otherwise. But what she’s built — an environment of care, listening, and loyalty — goes beyond price tags. She’s carried on a Charlotte way of building businesses upon a foundation of relationships.

She grew up on the same street as former Bank of America CEO Hugh McColl and several other notables from Charlotte’s past. Her house was often a gathering place for important conversations in the city. One reason she dropped out of Carolina for that year, she said, was that she struggled to figure out how she could possibly live up to her family’s civic legacy.

Their history here goes way back. Her grandmother (Richard’s mom) grew up on 36th Street more than a century ago. The steps to the home are still there — they’re among NoDa’s many “steps to nowhere” — in between what’s now Domino’s and Artisan’s Palate.

Laura’s grandmother worked as a receptionist for a real estate company downtown. People called her “the girl with the bedroom voice,” Laura says, because she had a beautiful voice. One day she was out for lunch and ran into a Swedish man who was in town from Chicago for business. They married, and he moved to Charlotte to become one of the first employees for C.D. Spangler Sr. They moved out to Meadowood Lane in south Charlotte, near where the Fresh Market is now. The roads were mostly dirt then. When Richard was 8, he got a pony for Christmas and rode it on Providence Road.

Laura still lingers over an old family photo of her grandparents walking shoulder to shoulder downtown — a reminder that before Capitol, before mayors’ offices and fashion magazines, the Vinroots were just another Charlotte family trying to make something here.

Now in her early 50s, Poole sees herself as an ambassador for the city that’s framed her family’s story. She’s simply carrying on a local tradition: If the thing you want doesn’t exist here, make it.

She just happened to want women to feel beautiful. Whether they work for her, buy clothes from her, or just meet her. When she travels to Europe, she can see a piece of clothing and picture it on one of her clients. She and her team go into their closets and help them edit their wardrobes. McColl, the former BofA CEO, credits Capitol with being key to recruiting companies and talented executives to Charlotte.

She says the local clients are unique. They don’t care about brands as much as people elsewhere do, and they don’t want clothes they’ve seen on others. They want to stand out as individuals.

“Is it beautiful? Is it different? Does it feel original? Does it feel like me? Is it appropriate to the occasion?” she says her clients ask. “And I know that is unlike anywhere else, probably in the world. I just think it’s a particularly sophisticated woman with great taste. You will not find better-dressed, more beautiful women than in Charlotte.”

When I asked why she didn’t move to New York or Paris or some other mega-fashion capital, she laughed. She doesn’t understand the clients there. She understands Charlotte.

“I think Charlotte is particular … I think it’s unusual. I don’t think most places have the same spirit of wanting you to be successful,” she said, sitting in Capitol’s courtyard, against a vertical garden designed by French botanist Patrick Blanc. “The community really wants to support that. They want Charlotte to be better. They want it to be more interesting.

“I know I couldn’t have built this anywhere else.”

A few years ago, at that anniversary gala with January Jones and André Leon Talley, Richard Vinroot, the former Charlotte mayor, walked around asking designers from France and Belgium a question: “Why are you here?”

“Well, Mr. Vinroot, in our business there aren’t that many nice people,” one of the designers told him, “and your daughter’s a really nice person.”

It was a sign that even as the city works through complexities and tensions that come with growth, even as it outlives the people who helped build it, the old staircases remain, and goodwill is still Charlotte’s most valuable export.