Last Sunday around 2 p.m., Kenya Joseph was terribly frustrated with the lack of engagement on her social media posts about the upcoming SNAP benefits crisis. She wanted to share facts over emotion, practical ways to help over political arguments — things algorithms tend not to reward.

Joseph, who serves dual roles as founder of Hearts and Hands food pantry and as board chair for the Charlotte Food Policy Council, turned to her little-used account on Threads and typed.

“I run a large food pantry in Charlotte, NC,” she wrote from her account @hiddenhippiealchemist. “Help us help. I’m talking to everyone who could, not the folks who need our assistance. We are happy to help and at the same time under siege. We can all get through this. Together.”

That night, her phone buzzed. Her post received about 10,000 views, exponentially more than she ordinarily sees. By midweek, she’d become a spokesperson of sorts for food pantries and a primary source for information on food assistance as the November 1 SNAP pause loomed amid the government shutdown. By Thursday, she was speed-walking through Hearts and Hands’ west Charlotte facility while a tractor-trailer full of food items arrived.

She also spent the week leveraging her role on the food policy council to advocate for county funding covering $50 for needy households at local farmers markets. Yesterday, the first day of the pause, Mecklenburg County farmers’ markets served 640 SNAP participants, Joseph says, a significant increase over a typical week. Davidson’s market alone saw a 500 percent increase in its average monthly users, the market posted.

After the markets closed yesterday, Joseph rushed to a town hall forum she’d organized, where she spent two hours explaining the food-assistance landscape. Meanwhile, she and everybody in that world were monitoring the series of legal rulings that ordered the federal government to release at least some SNAP payments early this week.

“It has been a doozy,” Joseph told me.

Of course, it’s been a doozy of a year for everybody in her field.

The list is almost too much to detail in a single story: This spring, the USDA cut nearly $1 billion from food-assistance programs. The summer brought the passage of the Big Beautiful Bill, which includes $186 billion in cuts to SNAP over the next decade.

Then, the federal government shut down on October 1, and that dragged on and on, with warnings that benefits would expire at the end of the month. About 140,000 people in Mecklenburg County, and about 43 million in the U.S., qualify for some food assistance. The pause would also strip billions from the national and local economies; Walmart makes about $2 billion a month from SNAP, according to Newsweek.

Still, Joseph struggled to get people’s attention. The issue barely registered through much of October; Google searches for “SNAP” were low and flat until exploding last week.

Then it became a political flashpoint in the shutdown debate. Vice President J.D. Vance noted that “The American people are suffering, and the suffering is going to get a lot worse,” before blaming Democrats for the shutdown. North Carolina Attorney General Jeff Jackson, a Democrat, joined a multi-state lawsuit pushing the administration to release $6 billion in reserve funds to keep SNAP running in November. A federal court sided with the plaintiffs, ordering the government to tap contingency funds.

So yeah, “doozy” seems appropriate.

The long-range message for food-assistance programs seems pretty clear: They’ll have to adjust to the new economic reality, or risk folding. But this week’s threat of a sudden cutoff raised a sharper question: How many people will go hungry while the safety net wobbles?

Joseph, whose multiple roles place her at the center of the swirling funding waters locally, has a chilling outlook for the worst-case scenario.

“If SNAP doesn’t come back, well, that’s going to lead us right into civil unrest,” she told me. “Because you’re literally dampening people’s ability to eat, and every single person on this planet needs to eat.”

I met Kenya Joseph five years ago, in the summer of 2020, outside Roof Above, where she helped people at the homeless encampment known as “tent city.” She was a no-nonsense person — a New York native who sugarcoats nothing and has little patience for pleasantries in a time of crisis.

So when I sought someone to help me understand the SNAP cutbacks, I called her. Within minutes of reconnecting, it was clear her straight-shooter personality hadn’t changed. The difference now is her influence.

The Hearts and Hands food pantry, small in 2020, has grown out of its Huntersville space into a larger building out near I-85 and Brookshire Freeway. It now serves about 2,000 people a month, making it one of the largest food-assistance programs in the county. She also became a board member and eventually chairperson of the Food Policy Council, the nonprofit that administers the county’s SNAP “double bucks” program.

That program uses public money to match up to $50 for every dollar an eligible SNAP recipient spends at a local farmers market. In other words, if a person spends $25, they can purchase $50. It’s been helpful not just to local residents in need, but to local farmers seeking stable markets.

“We have a handful of farmers that get thousands of dollars through EBT customers,” Davidson Farmer’s Market Manager Courtney Spear told me on Thursday. “But they’re now potentially not going to get that anymore.”

Joseph says the program has led to $100,000 going to farmers each year since it started in 2022.

Naturally, that’s where she focused when she knew the federal SNAP pause was coming. She worked with Mecklenburg County to keep the program going. Eligible people could go to the farmers market yesterday, show their EBT card, and receive $50 in tokens to spend. A small gesture, but something.

Joseph, for sure, will keep pushing.

“She’s like Charlotte’s food referee,” food policy council board member Erin Bradley, who works at Freshlist, told me on Friday.

The tumultuous week underscores how much things have changed since the U.S. first tiptoed into federal food assistance more than 80 years ago.

On Feb. 1, 1940, members of the Charlotte Retail Growers’ association met to explore bringing the national food-stamp plan to Mecklenburg County. They predicted a 50 percent increase in food consumption and thousands of dollars in local wholesale and retail business.

The program launched to rave reviews on March 10 of that year, with A&P grocer running an ad in the Observer that said, “How Government Food Stamp Program Helps Every Family in Mecklenburg County.” Even wealthy families could benefit, the grocer noted, because the program pointed them to surplus foods that they could find at a discount.

From March 12-26 that year, the program injected $12,080 into the local economy and served about 1,400 people. Federal inspectors praised Mecklenburg, saying that issuing officer J. Latimer McClintock and his team kept exceptional records, and that this was the only office in the country where they found every item balanced perfectly. (When I read that line in the archives, I thought of Joseph, who used the word “accountability” about a half-dozen times in our 90-minute call last week.)

That initial program ended in 1943, when the federal government decided that farmers and the national economy were in better shape. Food stamps returned in 1961, and President Lyndon Johnson made them permanent in 1964.

Yesterday would’ve been the first time the benefits were halted since then.

But even during the initial program, one Observer columnist presaged the debate to come: “Many of the poor not on relief refuse food stamps. It seems the price is too high when it includes self-respect.”

As the November 1 deadline approached, conservative influencers echoed that sentiment, arguing that SNAP recipients just didn’t want to work, despite strict work requirements for recipients who don’t have kids. A Washington Post analysis shows that in 2023, 75 percent of people receiving SNAP fell into four groups: children, people over 60, people under 60 with disabilities, or full-time caregivers.

Also, it’s not just an urban issue. While Mecklenburg County has the largest total number of SNAP recipients in North Carolina, they make up only about 11 percent of the population here. By contrast, about 80 counties have higher participation rate. Robeson County, for example, has a 33 percent participation rate.

Regardless, people working in food assistance like Joseph are desperate to steer the conversation away from partisan gridlock and toward real solutions.

“Neither side can hear each other at all,” she told me “There’s all cross talk. … The rhetoric has to change. Someone has to lead in a way that we’re actually getting the message through. Even on social media, they’re segmented.”

Joseph found her space on Threads, a platform that certainly leans progressive, but not as apocalyptic as Bluesky, and far less incendiary than X.

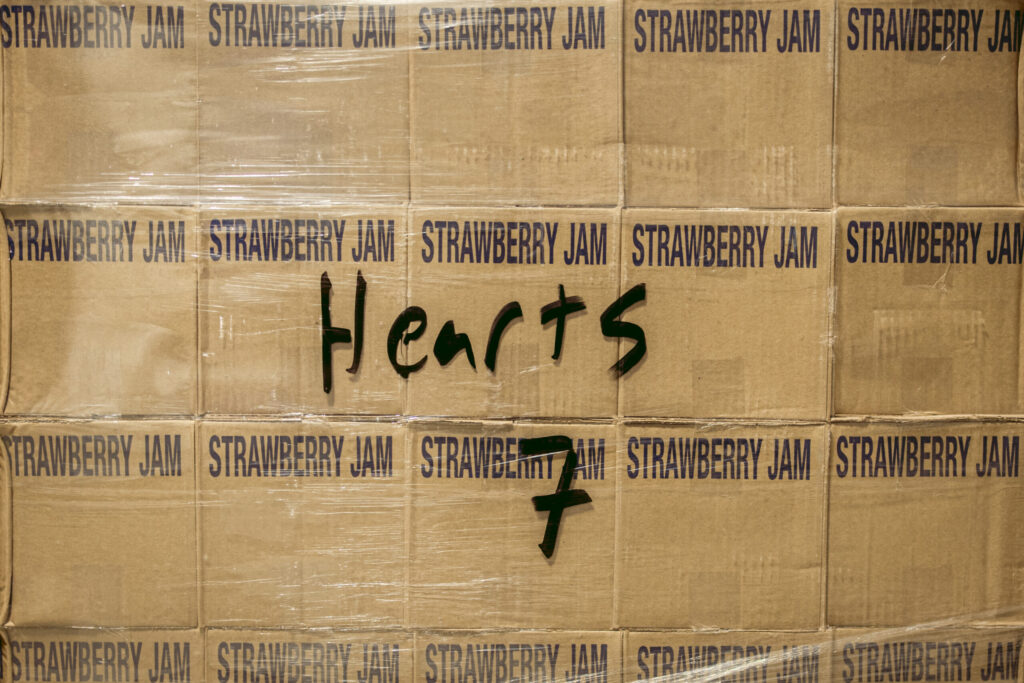

Her posts helped lead to a 70 percent bump in food donations last week, and a 30 percent spike in monetary donations. On Thursday, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent a tractor-trailer with 26 pallets of food. One new Threads follower became a volunteer, and Joseph says the existing staff likes her so much they want to hire her full-time.

Joseph is blunt about the most effective donation: It’s money. Yes, H&H has an Amazon wishlist and will take any food donation, with gratitude. But the organization prepares boxes for its 2,000 recipients, and money gives them the flexibility to buy what’s needed most.

“It’s not helpful if someone gets a box of onions, cake mix, and a tomato,” she said.

That’s an extreme example. Here’s one, though, that has become a running joke for her team in a rough time:

Peanut butter.

“People donate peanut butter,” she said. “For some reason, no one ever donates jelly.”

Then she stopped herself. Not “no one.” Hearts and Hands partners with Cannon School, a K-12 school in Concord. Sometimes they’ll run a food drive there and get jelly.

“The kids get it right away,” she said. “When the kids do the food drive, we get the best stuff.”

As I typed that last quote on Friday, a robocall from Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools popped up on my phone, assuring that students’ breakfast and lunch programs would not be interrupted. It all seemed like a metaphor. In a world of scarcity and shifting priorities, peanut butter still needs jelly. They’re better together, and even a kid can figure that out.