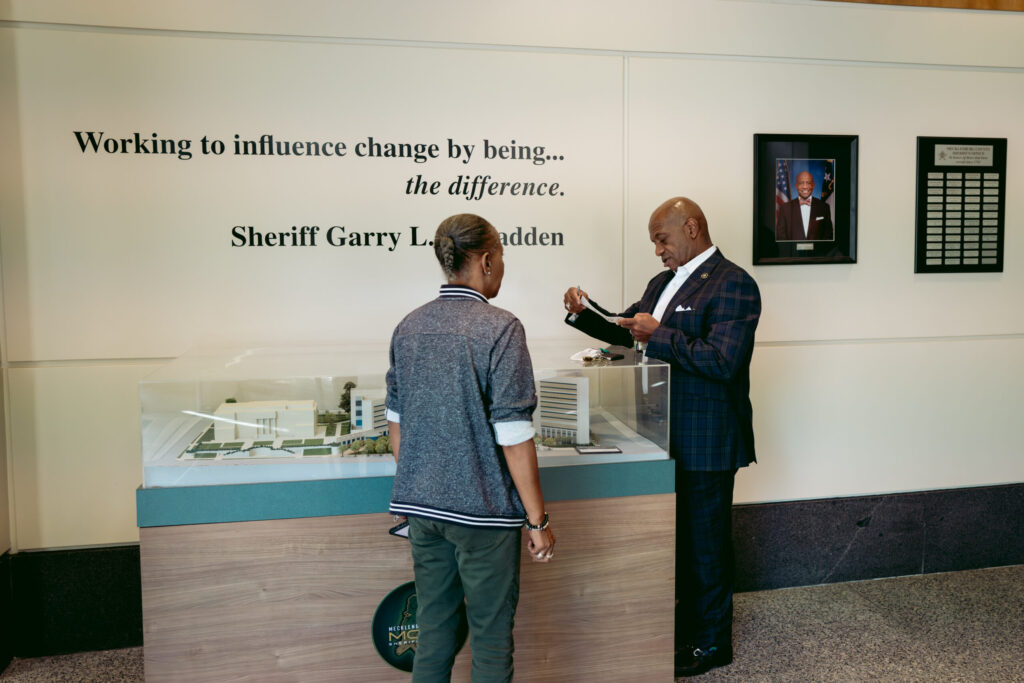

“Is that Mr. Garry McFadden?” a woman shouts from across the jail’s lobby.

The sheriff’s about to enter the secure hallways, but when Garry McFadden hears Garry McFadden’s name, Garry McFadden stops.

The woman speed-walks toward him, breathless. She’s a DoorDash delivery driver, she explains, and she’s just dropped off lunch for some jail employees. “And I’m slapped with a $125 ticket,” she says, on the brink of tears. “That’s the reason I refuse to take food over here.”

He tells her parking tickets are out of his jurisdiction. But he takes the paper, jots down his phone number, and tells her to have the issuing agency call him directly. “The People’s Sheriff,” as he calls himself, will handle it.

“Thank you, darlin’,” she exhales. “I appreciate you.”

Issues tend to track down McFadden. Seven years ago he was a semi-retired CMPD officer and widely regarded as one of the most successful homicide detectives in America. He solved about 600 murders in his career. Got his own TV show for it. But since becoming Mecklenburg’s elected sheriff in 2018 — a job that puts him in charge of more than 1,000 employees who run operations at the jail and courthouse — he’s become one of North Carolina’s most controversial public officials.

In August, a chief deputy resigned and issued a scorching letter that accused McFadden of “backstabbing, lies, disrespect, and false narratives,” and said his time in the office was the worst year of his career. That letter came nine months after the previous chief deputy resigned the same way, with similar words, accusing McFadden of creating a “third-world dictatorship.” And on top of all that, in November 2024, Mecklenburg’s first Black sheriff issued a public apology after WBTV unearthed a recording of him using racial slurs.

Still McFadden tells me he’s considering a run for reelection next year. Some well-known opponents are emerging, including CMPD Sgt. Ricky Robbins, who’s backed by former Carolina Panthers Luke Kuechly and Chuba Hubbard, and former CMPD Chief Rodney Monroe.

I spent nearly six hours with McFadden this past week, hoping to make sense of the emotional dust cloud he whips up in others, and to see if he wanted to settle any of it. He’s long had support from a motley mix, from homicide victims’ families to people who’ve committed homicides, from Republicans and Democrats, from celebrities to entry-level jail officers — and he’s had detractors at all those stations, too. He’s been called “Uncle Garry” for decades, but now that he’s in charge of hundreds of people, his family-patriarch style of leadership would make a corporate HR rep shudder. Still, most employees we encounter at the jail shower him with affection. “He’s like my uncle,” a detention officer says.

So yes, some people really like him and some people really don’t, but in his view, another person’s opinion of him says more about the person than him. He’s just … Garry McFadden.

“I don’t have any issues,” he says. “People have issues. I don’t have any.”

We started with a wavy three-hour sit-down interview in his office on Tuesday. He was theatrical in one moment and sincere the next, friendly then furious, complimentary toward supporters then scathing toward detractors. At one point he said, “I put no awards on my wall,” then pointed to awards on his wall.

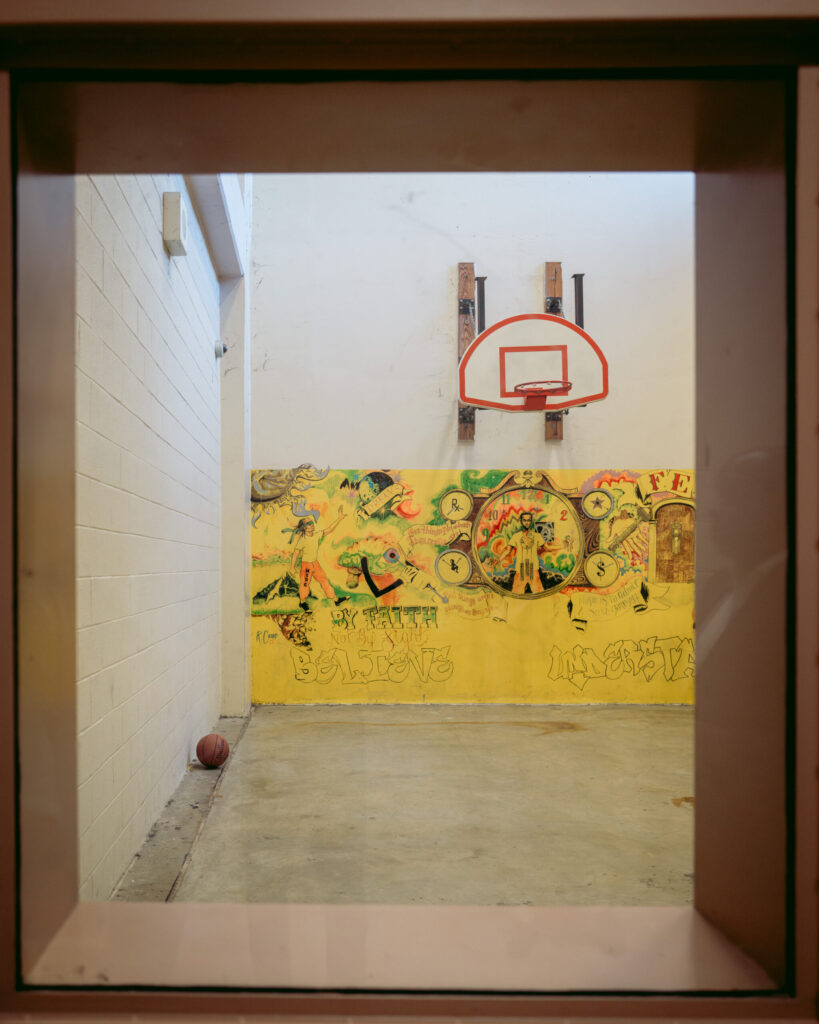

He ripped the media for not covering “positive” stories — a child-friendly visitation room, a business school that helped a former inmate launch a coffee truck, the first voluntary psych unit in North Carolina, a restoration program that reduces the caseload for psych hospitals, a recording studio to help mental health, and internal data showing a lower recidivism rate — and said the “negative, negative, negative” wears on his staff, not him.

In the jail, detention officers gave him hugs and offered him blueberries from their lunch, while residents gave him fist bumps and begged him to order Domino’s. (He didn’t order the pizza, to be clear.)

When I asked him about the accusations of his “dictatorship” or the “toxic” work environment, he flipped it around on me: “Are you a good husband? Are you a good father? Are you a good reporter? What would people say? And who would we believe?”

He said any office of 1,000 employees would have a range of opinions about the boss. He said we could focus on what a few former employees say about him, or on commendations from former presidents Biden and Obama. He noted his friendship with pro wrestler Ric Flair. He also gave a rather spot-on impression of Humpy Wheeler, the famous “P.T. Barnum of Motorsports” who died in August, and who told him he should run back in 2017: “Garry, fight ’em, Garry. Fight ’emmmm,” McFadden said Wheeler used to tell him.

About midway through our conversation, as he criticized the press, I turned it over to him and asked him to be the reporter: “You solved 600 cases,” I said. “Where would you start your interview with Garry McFadden? What would you ask him?”

“Tell me about first grade,” he snapped. “Tell me about fourth grade.” Soon he was in a full performance, asking and answering his own questions, turning his head toward a wall as if he were picturing critics. I didn’t interrupt him.

According to the timestamps on the audio transcript, Garry McFadden’s interview with Garry McFadden lasted for 34 minutes.

Why does any of this matter anyway, beyond the spectacles?

Sheriffs are elected by the people, so they typically speak to some larger truth about a place. They also tend to know the larger truths about the place. If roads are out due to storms and flooding, sheriffs in rural counties often know the only way around. If a cat gets stuck in a tree, firefighters may get it down, but the sheriff knows the cat’s name.

Garry McFadden is, in some ways, a mirror to Charlotte. Well-dressed, fueled by relationships, governed by give-and-take, eager to be celebrated for triumphs, uneasy and pretty defensive about flaws.

The main news here last week was the August 22 murder of 23-year-old Ukrainian immigrant Iryna Zarutska on the light rail in South End. The man charged with stabbing her, 34-year-old Decarlos Brown, had served five years in state prison from 2015 to 2020, and twice landed in Mecklenburg’s jail after that. He had severe mental illness; his mother told WSOC he’d been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

I brought up the case with McFadden, in the context of his mental health and rehabilitation efforts. I asked him how we help people who’ll make the most of second chances, while protecting the community from the truly dangerous.

“How do we solve for both things?” I asked.

He took the question off the page: “The majority of his time is spent in his community. … So we take that, the time that [Brown] spent with us, versus the time that he is with the community: Who failed him? I didn’t fail him. The community failed him.”

I hadn’t suggested that McFadden failed anyone, but he heard a hint of blame. To be fair, we’d set up the interview before that homicide. I’d called him the previous week, a few days after the most recent chief deputy’s resignation went public. McFadden said he’d have to think about the value of sitting down, to him and me.

The last time I’d seen him was a year ago at, of all places, the Baltimore airport. We caught up briefly and said farewell, but about a minute later he doubled back to hand my son a sheriff’s pin. It made his day. “Memories are important to me,” McFadden says.

“The only reason I’m doing this is because of that airport incident, with me and your son,” he said when I arrived in his office last week.

He then tried to size me up. “How much time would you say you’ve even spent preparing for this?”

I told him I’d read nearly every local newspaper story written about him since the first one from 1995. I mentioned one case from 1999, when a 5-year-old boy died in a pool and his 9-year-old brother was charged with strangling him. McFadden immediately remembered the older brother’s name, and added that he saw him recently. He even told me the date of the killing.

“Pretty good memory, huh?”

I nodded. Then, in a screeching transition, he threw the calendar back 300 years.

“How much do you think my great-great-grandfather was sold for?” he asked.

“Eight hundred fifty dollars,” he answered. “He was 59 years old. I’m 95 percent Nigerian, 5 percent Scottish. How about if I tell you that I know the day that the slave owner arrived … to South Carolina on the shores of Charleston, Mount Pleasant? May 29, 1762.”

McFadden is from Elliott, South Carolina, about an hour east of Columbia. His family still lives near the same land his ancestors worked while in bondage. He returns to the fields every fall to pick a boll of cotton, and he brings it back and puts it in a bowl on a table in his office. The cotton bowl sat between us during our interview. He said he’ll return to the fields this fall, alone, and make his final decision on whether to run again.

He pointed to the wall on the other side of the room, with pictures of his family, past and present.

“I don’t do this for politics,” he said. “I do this because people require me to do it.”

We’ll get back to that.

His first controversy as an officer was over doughnuts.

McFadden graduated from Johnson C. Smith University in 1981. After landing with CMPD, he realized that relationships were everything in policing, and that the best way to build relationships was to be memorable. To make an impression. So he’d drive around to bus stops in some of Charlotte’s most troubled neighborhoods and hand out Krispy Kreme. His supervisors gave him a demerit and told him to stop, but he found other ways. He handed out Butterballs at Thanksgiving and went to neighborhood cookouts. Even today, he sends money on Cash App to people like a mother who wanted to rent a bounce house for her kid’s birthday.

“I always want to make an impression that I care, because I do,” he said.

There’s as much in it for him as them, though, in the long run. As a detective, he always figured that he’d need a future witness for a crime, and those kids or neighborhood grill masters would help him. The philosophy still guides him. Critics rail against the programs he’s created in jail. Confinement should be more punishment than fun, they say. How could he joke about Domino’s with someone who steals cars or assaults people or worse? Because, he says, that inmate’s mother might remember his kindness, and she might be there for him one day. Or that person awaiting trial could be set free, and society will need a contribution.

“What if it’s bone marrow, your daughter’s bone marrow, and he’s the only person that matches that,” McFadden says. “How would you want me to prepare your neighbor? I’m just trying to make better citizens.”

His unorthodox approach worked in his detective days. He investigated more than 800 killings in his career and solved roughly 90 percent of them, according to old newspaper accounts. Families asked him to speak at funerals. Outlaw bikers once sent him a card. He was a character even when no one was watching: If he got a call in the middle of the night, he’d listen to Limp Bizkit or Slipknot or some other heavy metal on the way to the scene.

After the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, Missouri in 2014, McFadden helped launch Cops & Barbers, which brought people together for tough discussions on race and policing. Several national outlets picked up on the story, and the Obama administration recognized the program as a highlight of 21st Century policing.

Television found him. I Am Homicide, which ran on Investigation Discovery in 2016 and 2017, cast McFadden as himself: sharp suit, clipped phrases. It built his reputation beyond Charlotte, cementing him as not just a detective but a performer.

If homicide had made him a star, though, the sheriff’s office made him a target.

He campaigned on ending the county’s participation in 287(g), a cooperation agreement that allowed deputies to act as federal immigration agents, and did so on Day One in office. He argues that trust makes communities safer because immigrants will report crimes and bear witness to them.

His defiance, though, started six years of battles with ICE and the Republican-led General Assembly. Last year, lawmakers passed a law mandating sheriffs to honor ICE detainers. This year they tacked on HB 318, which requires sheriffs to hold undocumented immigrants for longer and expands the list of crimes that require status checks. So, McFadden’s open defiance of a voluntary program in 2018 helped set the stage for mandates.

The new law goes into effect on October 1. McFadden took us to the intake area of the detention center on our tour. When he arrived at the intake room, he approached the team that processes arrestees’ initial paperwork, which includes questions about a person’s citizenship status. “October 1,” is all he said. And they replied, “October 1.” McFadden grinned and said, “I’m gonna bring y’all food.”

McFadden describes the moment in 2018 where he realized he’d be the face of the tension between urban law enforcement and ICE in mythic terms: “I put on my armor, my shield, and my sword. This was going to be a battle.”

The battles continue elsewhere. State jail inspectors have cited Mecklenburg’s detention center for violations. More than a dozen people have died in custody in the jail since 2018. McFadden counters that by asking how many people die in hospitals with full-time medical teams right there. Still, he settled with the family of a boy who died by suicide in the jail for $550,000 earlier this year. In February, the office also settled that lawsuit over concealed carry permits for $5,000, or the attorneys’ fees for the plaintiffs. In July, the sheriff’s office issued an apology to a Kannapolis family after they saw that a loved one’s accused killer highlighted in a feature story about the jail’s new recording studio.

Then there are the administration issues. A Charlotte Observer investigation earlier this year found at least seven former employees who said McFadden was an abusive and dysfunctional boss. One retired employee told the paper that McFadden is “the biggest narcissist,” and a fired detention center employee said, “He thinks he’s godlike.”

Former chief deputy Kevin Canty told WCNC last year that “it’s the most toxic environment I’ve ever worked in.”

McFadden said he can’t legally respond to the individual letters. One thing that emerged from our conversations is that he has a range of relationships, from familial to adversarial, among employees. The two deputy chiefs who’ve resigned had more than a half-century of service combined. McFadden admits that the closer a staffer gets to him on the org chart, the more pressure he puts on them. He says he doesn’t like surprises, such as learning too late that someone brought a gun to the courthouse. He still reads his daily emails on the detention center’s resident count. But the resignation letters indicate that with those closest to him, he’s crossed a line or multiple lines, even if he disagrees.

“Why’s it so hard to work for the sheriff?” he says. “I just want to know. I have to have this knowledge. I have to understand.”

Inside the detention center, the portrait of McFadden as a “dictator” is more complicated.

He moves through the place like a pastor in his own congregation. We see the cafeteria, the classroom, the kid-friendly visitation room, the mental health pod, the jail’s hospital, even the laundry room. Over two hours, we meet or pass more than 100 people, and if I had to guess, McFadden knows 90 percent of them on some personal level. He jokes with one officer about her trip to Atlanta, asks another about how his brother is doing, and yaks it up with a deputy who’s retiring in two months but intends to return to work here after that.

“Then what are you going to do?” he asked her.

“Work.”

“And?”

“Be great.”

McFadden continued with “And?” until she gave the answer he was looking for: She’d bring one of her daughter’s handmade cakes.

McFadden traveled to Norway and Germany before becoming sheriff to study their progressive prison systems. He quickly rolled out changes in 2018, dropping the name “jail” for “detention center,” and the term “inmates” for “residents.” He points out the cleanliness repeatedly on our tour, saying you can see your face in the floors and that you’ll never smell anything rotten.

When we arrive at the medical wing, the administrators tell me about the challenges of keeping people healthy when most arrive with a host of medical troubles. One woman was recently incarcerated at nine months pregnant. They transported her to the hospital to give birth. The father flew in from California, scooped up the days-old infant and flew back, while the mother immediately returned to jail.

Even against conversations like that, McFadden is all smiles during the tour. Staff freezes in place to grin back when they see him coming. The whole experience takes more than two hours, mostly because he talks to everyone.

This was Wednesday, the same day a recently hired detention center officer died in an auto accident while off duty in South Carolina. I told McFadden several times that we didn’t have to continue. But he kept showing us around until the last possible minute.

As we walk out, a captain is gathering the young deputy’s platoon to deliver the news. McFadden tells her to introduce herself to me.

She smiles and says she’s from New York, and that she’s a Delta.

“No, tell ’em how many times I gotta beat you in the head to do right?” McFadden laughs.

“A couple, you know,” she says, laughing back. “That’s what happens.” It’s all friendly and familiar, like a filterless family picnic. But still, it’s not hard to see why other employees might take it another way. But as I write out that quote, it’s reasonable to see why other employees might not. The line between “Uncle Garry” and “Sheriff McFadden” can be hard to see.

A few minutes later, as we leave the jail, the same captain comes back to wave him over. It’s time for him to console the deceased deputy’s platoon. So we say goodbye.

On January 29 this year, Garry McFadden was in Washington when his phone rang. It was an emergency responder who was airlifting his wife, Cathy, to Atrium Main in Charlotte. She had severe brain bleeding. The responder told McFadden he should come immediately. He started searching for flights. As it happens, that was the night a plane collided with a helicopter over the Potomac River. He and Cathy have three adult sons, one of whom is a flight crew member, but he wasn’t working that night. Instead he was driving to the hospital and saw the emergency chopper carrying his mother fly overhead.

Cathy spent more than two and a half months in the hospital and rehab. McFadden says he never left her, and worked and took his calls bedside. I asked how he managed that and he said, “Because I prepare for the battle every single day. Smile, laugh. I prepare for it.”

Next to the bowl of cotton from the fields where he comes from, McFadden keeps his father’s childhood shoes. His grandmother stuffed them with handkerchiefs and gave them to him years ago and said, “You can never wear your father’s shoes.” He took that to mean, be yourself.

“I’m not the former sheriff; I’m not the sheriff [who comes] after me. I’m just Garry McFadden.”

His office is full of symbols. There’s also a leather-bound notebook where he wrote the opening page of a memoir he intends to finish after he’s done being sheriff. It’s dated December 3, 2018, the day he was sworn in:

Garry McFadden: First African-American sheriff of Mecklenburg County. … I am thankful for my life, my health, my family. God has given me a mission. Hate will come to me in different color! I’m ready.

He was part of a wave of “firsts” for the city. Vi Lyles had become Charlotte’s first Black woman mayor in 2017, and Spencer Merriweather became Mecklenburg’s first Black district attorney in 2018, the same year McFadden was elected. McFadden is unquestionably not like his peers, including CMPD Chief Johnny Jennings. They’re all even-tempered, diligent, and averse to creating dust clouds. They’re the sort of folks who’ll probably curl up with a book in retirement rather than write one about themselves.

When I simply suggested to McFadden that he stands apart, he started swatting — maybe at me, maybe at them, maybe at the ghosts of the people who enslaved his ancestors, maybe at all of the above.

“We want to still mold him into Vi, Jennings, Spencer, and all them. I’m not them,” he said. “It’s all expected to be: if they’re quiet [and] they’re quiet, you’re supposed to be quiet, too. How dare you? You’re supposed to be quiet, too. You don’t know your place.”

He looked at me, a white guy, and said, “See you don’t get this.”

“When Black children speak well, you know what they say? Oh he speaks so well. He dress so nice. See we don’t want to go there. He dress so nice. He’s so well-mannered. We like them. Because they’re not outspoken. They’re nice,” code-switching his inflection for effect.

Then he unleashed.

“Find any one of them with more awards than I have. Find any one of them who’s more connected to the community than I have. Take a vote. Walk five of us in the community and see who the people [gravitate] to. Oh, Heyyy. Heyyy. Find out that.”

He paused and punctuated.

“The People’s Sheriff.”

Editor’s note: This story was corrected to say that the off-duty officer who died in a car accident last week was a detention center officer.