“Virtually every commercial transaction has within itself an element of trust, certainly any transaction conducted over a period of time.” — Nobel Laureate Kenneth Arrow, in 1972.

Each weekday morning, just after 7, my son sprints the quarter-mile to the bus stop. He’s marveled at buses and trains and all forms of communal commuting since he learned to walk. Now, the yellow bus is the highlight of kindergarten, a place where he tiptoes into independence and tries to understand all this “six-seven” talk.

On his first day as a bus rider, I was a couple minutes late to the afterschool pickup. Our trustworthy neighbors were there to greet their daughter, but the driver wouldn’t let our kid off into their care. Instead she held the bus while I ran up the sidewalk.

“I just want to be sure,” she told me, pointing at our neighbors, “in the future, you’re OK with him getting off with them?” Yes, I said. I appreciated the caution, but it was a reminder of changing times. I’m certain my kindergarten bus driver 40 years ago would’ve shoved me off into care of deer and squirrels if it kept her moving.

The small exchange got me thinking about trust, and how it’s cratered. Fifty years ago, nearly half of Americans believed most people were trustworthy, The Atlantic noted last year; today it’s under a third. Trust in institutions is worse: A Gallup poll shows that in 2002, half of Americans trusted the Supreme Court; now it’s barely a quarter.

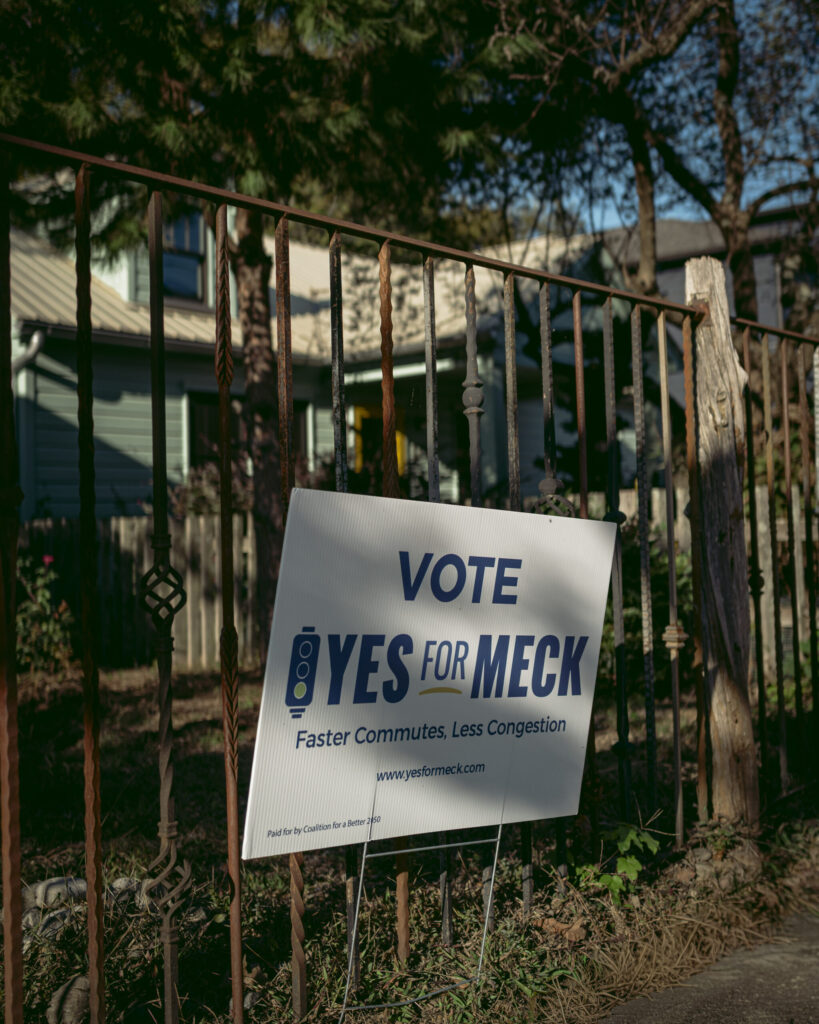

Into the distrust epidemic, Charlotte’s political and business leaders are asking people throughout Mecklenburg County to vote for a 1-cent sales tax increase on the promise that it will vastly enhance our transportation network and the overall quality of life here for decades to come. The proposal would raise $19 billion and could unlock $6 billion in federal funds over the next 30 years. About 40 percent would go to rail and transit, 40 percent to roads and sidewalks and bike lanes, and 20 percent to buses. A complex 27-member transit authority would run it.

Managers of all but one of Mecklenburg’s municipalities signed off on the plan, as did a bipartisan majority in the General Assembly. Proponents raised millions to convince voters, and my phone has the campaign texts to prove it.

They could take me off the list. This isn’t an essay to convince you — plenty of recent op-eds that do that, for or against — but given the distrust in media, it seems transparent to say I’ve heard the arguments and will be a yes. I grew up in a very rural area and lived in some rather depressing places, and I’ve come to believe that infrastructure investments, even imperfect ones, advance the overall health of our state. It’s vital, as the research firm Brookings notes, to keep urban economies moving and growing to subsidize investments in rural areas.

Several close friends oppose the plan. When I asked a longtime nonprofit leader and dear friend whether he supported it last week, he said, “Hell no. Why would I trust the city with all that money?”

That last part, the t-word, deserves a deeper internal look. Because a vote on a generation-spanning infrastructure plan is essentially a vote on whether we trust the framework of the proposal, and whether we trust future boards and policymakers to implement it with integrity.

The cliche is that trust is earned, not given.

City leaders tried to claw back trust last week, after a year of turmoil. Mayor Vi Lyles touted an independent investigation that cleared the council of “unethical, immoral, or illegal activities” in its settlement with the police chief. Later in the week, CMPD released its quarterly crime statistics and stressed how, despite several recent high-profile murders, violent crime has fallen 20 percent from last year.

Both announcements landed with shrugs and an online chorus of “Yeah, right.”

There are many reasons for that reaction. But what if, I wonder, we each considered whether our own perspective on trust is framed by a window, or a mirror?

A fascinating Financial Times analysis this summer showed Americans have become less dependable, less agreeable, and more anxious — especially since the pandemic. One takeaway from that might be that a population primed for negativity not only distrusts its leaders, but itself.

Robert Dawkins, a brilliant and informed community advocate, leads the opposition to the transportation plan. He’s said that years of unfulfilled promises — the failed Red Line expansion after a 1998 transportation tax increase, the cost overruns of the Blue Line, and listless efforts to curb displacement along transit lines over the years — drive his doubt.

“If I hadn’t been the Robert who saw all of that, then I’d be more optimistic about this, and I’d believe in it — and I’d believe in the Easter bunny and everything,” he told me this summer.

We can all agree that when someone compares transportation promises to an egg-laying rabbit, trust is an issue. But it’s also a projection that Charlotte’s future boards will lack the competence or resources to follow through on the plan’s promises. Which is as much an indictment of the electorate as it is anyone elected.

It also accepts that current and future leaders haven’t learned from past mistakes, like how the 1998 sales tax ran out of money during the recession. Council member Ed Driggs, a Republican whose background is finance, told me that he’s run some numbers himself, and he believes the financial projection for this sales tax are “fairly conservative.”

“In my own opinion, if you don’t pass this and make those investments, the quality of life will suffer,” he said.

Attorney Kimberly Owens is running for the open District 6 council seat against Krista Bokhari. Owens, who says she wants to restore faith in democracy for her own children, supports the transportation plan. But she understands why people are dubious. She talked about “trust equity” and the need to build it.

“We need to be just grossly competent about a number of things before people are going to be like, ‘Yeah, let’s pay some more in taxes,’” she told me.

We’ve been here before.

In 1975, Mecklenburg County voters held the future of the region in their hands. They were considering a $55 million bond referendum to replace the 21-year-old terminal at Douglas Municipal Airport. Supporters faced serious trust headwinds: The U.S. economy was at the tail end of a recession. Eight months earlier, Richard Nixon resigned. And bond opponents questioned “City Hall’s credibility.”

A letter to the editor titled “Airport expansion is another fiasco” said, “Who does all the flying? Certainly not the middle-and lower-income majority of Charlotteans who as taxpayers will have to bear financial responsibility for the airport bonds.”

Opponents in 2025 make similar arguments, saying that the tax is regressive, meaning it would cost poor people a greater percentage of their income. One difference this time, though, is that the Black Political Caucus endorsed the 2025 transportation referendum. The group did not support the airport renovation 50 years ago.

Into that sea of distrust in 1975 stepped Harvey Gantt, who’d later become Charlotte’s first Black mayor. Today he’s a leading champion of the transportation tax. Back then, he was a newly appointed council member trying to rally Black voters to support the airport proposal. It didn’t work. The measure failed due to overwhelming opposition from two groups with historical reasons to distrust the government — Black voters in the city, and people in recently annexed suburbs.

That left the city in a bind. New federal rules created competition among airlines that would almost certainly end with some airports as winners, and others as losers. Charlotte leaders desperately wanted to be on the winning side.

“I want Charlotte to be a real, honest-to-goodness city — not like Atlanta — but with planned growth,” Ben Douglas Sr., the “father of aviation in Charlotte,” who helped found the original airport, told the Observer at the time. “No area, whether it’s a big town or a crossroads village, can prosper without two things — you’ve got to have water and transportation.”

Three years later, a new bond referendum hit the ballot: This was for $47 million, which would trigger an additional $12 million in federal funding. They overwhelmingly approved it, but by then, they were late. When the new terminal opened in 1982, traffic was so high that leaders were already looking for ways to add a third concourse.

The airport, of course, has become one of the busiest in the world. It is “the most important economic engine we have,” developer Johno Harris told me last spring. Consider this: The 1954 terminal could handle only about 800,000 passengers per year. The current Charlotte-Douglas handles about 60 million.

Without question, had voters not eventually come around to financing the airport’s expansion, many of us likely wouldn’t be living here today, arguing for or against the 2025 transportation expansion.

In my previous job as Southern bureau chief at Axios, I oversaw our team in Nashville, which gave me a windshield view of that city’s transportation referendum last year.

Six years earlier, in 2018, voters rejected a massive referendum that would’ve raised the sales tax by one percent over time (bringing it to 10.25 percent overall, higher than Mecklenburg’s proposed 8.25 percent), to pay for light rail and bus rapid transit. Opposition from the anti-tax right and displacement-wary left coalesced. And a scandal involving the Nashville mayor’s affair and misuse of public funds just months before the election undercut trust in city leadership, and sank the plan.

But in 2023, a fresh, nerdy, bus-riding dad named Freddie O’Connell became mayor. In early 2024, he proposed raising the sales tax by a half-cent for a scaled-back transportation plan that focused on buses, sidewalks, and pedestrian safety. That referendum passed by a 2-to-1 margin last November.

Pretty simple recipe: digestible plan, reliable messenger, high-turnout election, and trust. Those who oppose Mecklenburg’s transportation bill this year have said that if this referendum fails, the county could come back with a similar, pared-down approach.

Of course, it’s hard to quantify what Nashville lost by waiting six years. Charlotte’s economic development folks say that businesses looking to relocate headquarters here ask whether we have an infrastructure plan. Some say Nashville has fallen down on the list of Charlotte’s top competitors for new business, behind Dallas and Atlanta.

“There is no place in America that is a better place to be right now than [the Charlotte] region,” former mayor and U.S. Transportation Secretary Anthony Foxx said at the Tuesday Morning Breakfast Forum in July. “You have an opportunity today to have a sustained and deep engagement on shaping this region. And if you do it well on transit, it gives you an opportunity to do it well in the broader sense.”

Before we close, one more thing about that Financial Times story.

The decline in conscientiousness is most dramatic among young people, ages 16 to 39. It’s fallen among people in the 49-59 age bracket slightly, and remained pretty steady among people over 60. The rise in neuroticism follows the same trend — skyrocketing among younger people.

Studies show that Gen Z is less optimistic than any other generation about the American Dream. The reasons range from smartphones to housing costs to political divisiveness. Cause aside, though, the effect is a loss of hope.

So I go back to our kids, who know nothing beyond the world we curate — one free of television news, one where “outside” is a threat-free heaven where they can collect acorns and ride buses and meet friends.

Earlier this month, at the Leading On Opportunity summit, one speaker brought up a woman he saw bathing her children in a truck stop bathroom. I couldn’t stop thinking about how, if a majority of young people feel such hopelessness, how might a child in those circumstances feel?

For the well-off, faith is an option; for the less-fortunate, it’s the last resort.

The bus driver wouldn’t let my son off until she was sure he’d be safe. She was asking for trust, and in the pause she created, everyone had to show who they were. This referendum feels like that, a pause at the door, a chance to decide whether we still trust one another — our neighbors, our business and political leaders, and hell, ourselves — to head down this path together. Because if it passes and achieves its lofty mission, we might create a little hope for the ones who’ll come after us, and if it turns into another series of broken promises, we risk leaving behind only strangers.