The seagulls were all around him.

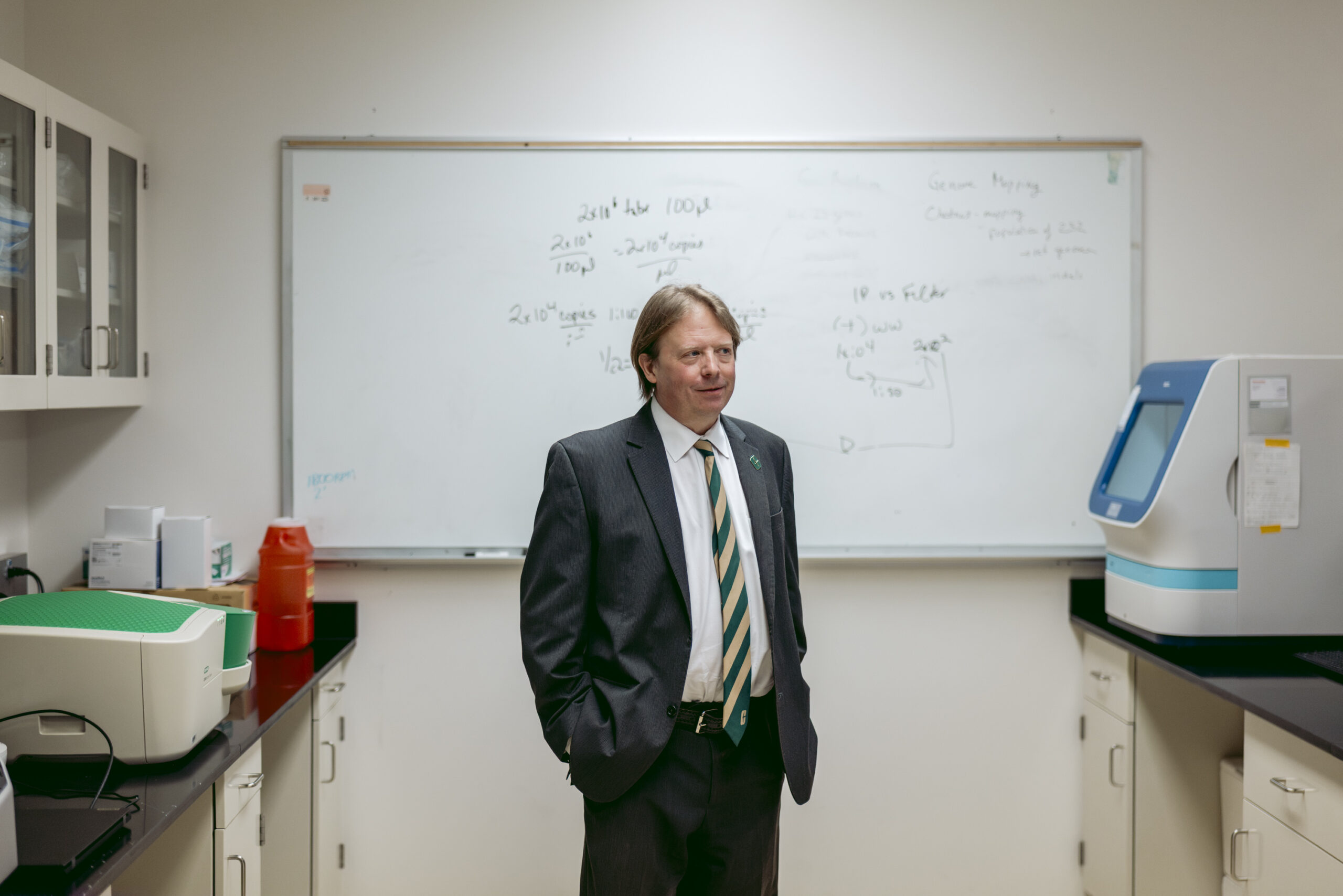

Dan Janies had flown to Alaska to talk about starfish, not birds. A distinguished professor at UNC Charlotte, and without question one of the most intelligent people in our city, Janies was there to help a student present research on starfish, which share a common ancestor with humans, and how they can regenerate limbs while we can’t. But that’s another story.

In between all the regenerative tissue talk, Janies and his student went to a Juneau beach to fish. The weather was ideal, 70 degrees, so they decided to have a picnic lunch.

There was one issue: the seagulls.

Janies knows too much about birds to relax around them. He’s one of the world’s leading experts on bird flu, or H5N1. Recently the virus has become “promiscuous,” jumping from birds to mammals, including humans. Now, when Janies sees a bird he assumes it has the flu, and that he could catch it with direct contact. So when he saw his student picking up feathers on the beach, he said, “We’re going to go back into town and wash our hands.”

At last count, H5N1 had been detected in more than 200 species of birds and mammals, including at least 70 farm workers in the United States in recent years. Dairy farms have been especially vulnerable over the past year, and the belief was that the farmworkers got it while milking cows. But this week, the New York Times reported that a new study, not yet peer reviewed, found that the virus was on milk droplets, which means it’s likely on respiratory droplets, which suggests bird flu may be airborne, which would be a concerning but clarifying step in the virus’s evolution.

It’s no cause for alarm, Janies says. The virus hasn’t yet jumped from human to human, but the study may explain how cows are passing it to people. Most of the human cases have been mild — pink eye is a symptom — though one elderly person who had underlying conditions in Louisiana died from it. Still, Janies has spent much of his career studying the possibilities of the next pandemic. And with only a month until peak migratory bird season, when tens of thousands of birds pass through Charlotte each night, his research shows that the avian flu spikes in spring and fall. He has modest advice:

Think twice about eating at picnic tables with bird droppings. Wear protective equipment if you’re working with farm animals or hunting for ducks this winter. Don’t drink raw milk. And, of course, as Janies told me in a visit with him two weeks ago, “Washing your hands has been good advice for decades. For centuries.”

Charlotte, you may not know, is home to a leading bioinformatics and genomics department, and their work has helped move UNC Charlotte into the top tier of U.S. research institutions.

Janies is co-director of the CIPHER Center, short for Computational Intelligence to Predict Health and Environmental Risks. Opened in 2023 on the top floor of the university’s bioinformatics building, the center fulfills Janies’ vision to create a collaborative space where computer science, biological science, and public health experts can work together, using advanced artificial intelligence to monitor what viruses are doing now and predict what they’ll do next. His team was among the first in the world to correctly predict the surge of the Omicron variant in December 2021. Today they’re using some of those tools to model how H5N1 is changing, and how well existing vaccines or antibodies might hold up.

That also puts Janies at the center of a revolution and a tension point in modern science, where speed and accuracy must coexist. The COVID-19 pandemic proved many things, among them these two competing forces: We want science to work fast, and we want it to be correct the first time. CIPHER leans on AI, but verifies results with human expertise and reviews.

“One day masks are important; one day they’re not. The public really got confused,” Janies said of the pandemic. “So I think the most important thing is, it’s part of your citizenship, to not put out things you don’t have. You might work a little faster than before, but as part of being a good citizen, put out things you really believe in.”

The marching band was playing Pharrell Williams’ “Happy.” This was late March, and Janies and I had taken the university bus from the CIPHER Center down to the heart of campus for a celebration of UNC Charlotte’s R1 status. The Carnegie Classification essentially means that this campus, which was cut out of a cow pasture 65 years ago, is now home to one of the top research institutions in the country. Only four other universities in North Carolina have the designation.

The dignitaries ranged from Chancellor Sharon Gaber to trustees to local politicians and business leaders. The party included green and white cupcakes, free T-shirts, and the ringing of the Old Bell.

UNC Charlotte has been called one of our city’s best-kept secrets, in part because its main campus sits 10 miles from uptown, and in part because of its outdated reputation as a commuter school. It still serves that local population, but Gaber’s been enhancing its image in her five years as chancellor. When she arrived in July 2020, one of the first calls from faculty and staff was to push for R1 status. It meant spending at least $50 million a year on research and awarding at least 70 research doctorates. The university hit both marks by 2023, and the R1 announcement came at least a year ahead of schedule.

“We are unstoppable,” Gaber told the crowd.

The R1 news, made official in February, came at a striking time in Charlotte’s story. It happened just before the opening of The Pearl, the medical school and research campus in midtown that’s the result of a collaboration between Advocate Health, Wake Forest University, and a number of other partners.

Together, The Pearl and UNC Charlotte’s R1 leap could make 2025 a year that will be remembered as the point where Charlotte’s identity shifted from a finance hub to a multidimensional city with science and research, where we’re known for exporting not just wealth but knowledge. From Banktown to Braintown.

Janies has been a catalyst, whether he realizes it or not.

He arrived at UNC Charlotte in 2012 as the Carol Grotnes Belk Distinguished Professor of Bioinformatics and Genomics. Before that he was at Ohio State’s College of Medicine, a much larger institution with much larger budgets. When we talked about that experience, he quickly pointed out that he’s from Michigan, went to the University of Michigan, and remains a diehard Wolverine. He also has a doctorate in zoology from the University of Florida, and spent years becoming an expert in zoonotic diseases, or viruses that jump from animals to humans.

In his office are pictures from his career, along with newspaper clippings of Michigan’s football victories over Ohio State. There’s a photo of him with former House Speaker Newt Gingrich, from his time at the American Museum of Natural History, where he built one of the world’s largest computing clusters. And there’s one from his testimony before the Senate in 2007. I asked him what his testimony was about.

“Coronaviruses,” he said. “It was a hearing called ‘To Forestall the Forthcoming Pandemic’ or something like that.”

Yes, a current professor at UNC Charlotte was testifying before Congress about coronaviruses, 13 years before a pandemic caused by a coronavirus hit. Then, when COVID-19 swept the world, Janies’ work accelerated. A turning point came on Thanksgiving 2021, when a postdoc named Colby Ford called him. Scientists had released the genome for the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, and Ford used artificial intelligence to model the “spike protein’s receptor binding domain.” He found that the variant could evade the vaccines people had been taking that year.

Janies was working in a library in his hometown in Michigan when Ford called. He immediately reviewed the work and found it was solid. So they posted their findings online. UNC Charlotte, in that moment, became the first to predict the Omicron surge that dominated headlines and disrupted schools and daycares throughout that holiday season and into the new year.

“That would have taken months in a lab,” Janies said of the computational analysis. “But by that time, Omicron would have already swept the nation or the world. So that got me very excited about what we’re doing.”

The breakthrough cemented the need for the CIPHER Center, which UNC Charlotte was already working to develop. Now that it’s open, the center is a bridge between scientists like Janies and AI specialists.

When Janies and I had our follow-up meeting two weeks ago, we talked about the potential pitfalls of artificial intelligence in its infancy. I recorded the interviews, which stretched nearly three hours in total, then dropped the transcripts into an AI platform and asked it to pull his most compelling quotes. The machines kept paraphrasing his words, no matter how many times I asked it to send me only direct quotes. And some quotes, it completely fabricated.

That’s what AI’s hiccups look like in my industry. In his field, one AI hallucination could trigger a false national emergency, or miss a real one.

Human evaluation, Janies said, will remain essential. Even with Omicron, a group in Canada calculated the structure of the spike protein “the old-fashioned way, using cryo-electron microscopy,” he said, then compared results with the UNC Charlotte model.

At 58, he still has a few concerns about AI, but he works at a university, and the energy of young people pushing him forward is one of his great joys. I asked him what might happen several generations from now, when the only people on earth are those who’ve grown up with AI.

“I think skepticism is going to be one of the most important human traits going forward,” he said. Then he continued. “I mean, it’s not new. Science is, a lot of revolutions have occurred. … Ulcers were supposed to be caused by stress, right? And then they found out it’s actually an infection, right? Immunotherapy for cancers is coming to the fore now, but the people who studied that for a couple of decades suffered a lot of ridicule, and then they got the Nobel Prize eventually.

“Science revolutions, or false starts and restarts, occurred before AI.”

Janies isn’t a scientist who seeks attention, but he knows that writing papers only reaches other scientists. If he wants to raise awareness, he needs to communicate findings and concerns widely. He’s done a number of social media posts, YouTube videos, and podcasts about H5N1.

He talks in layers, not soundbites. He can bounce effortlessly between the ethics of machine learning, the evolution of the bird flu, regenerative medicine, and the reasons people shouldn’t touch their faces with unwashed hands. There’s a quiet urgency to his words. Not panic, but awareness of everything that lives around us, whether we can see it with the naked eye or not, and a belief that science needs to stay ahead of viruses.

But that’s not all he knows. He’s also a father of a high schooler at Hickory Ridge. He’s a regular at UNC Charlotte’s football games.

When we took the elevator down from his offices a couple of weeks ago, we got to talking about the Michigan-Ohio State football rivalry. It’s the only game he makes sure to watch from start to finish each year, and lately it’s gone his way: Michigan hasn’t lost since 2019.

Or, as Janies puts it, “It’s been like 2,500 days since Ohio State won.” I looked it up afterward, and it’s closer to 2,100 days. Regardless, when you’re a scientist who’s on the winning side of a high-stakes contest, and you know momentum can change in the blink of a season, you just grin in the moment and say what Janies said next: “Every day is a blessing.”

Editor’s note: We corrected this story to show that the person who died from H5N1 in Louisiana was an elderly patient, not a farm worker.