Five years after he announced Charlotte’s first medical school, four days after opening it to the public for the first time, and one hour after delivering a speech to power players from across the state and country, Gene Woods picked up an electric guitar.

This was Thursday night, the final evening of a long week of celebrations for the opening of The Pearl, the medical school and research campus that many leaders believe fills our community’s most glaring void.

Earlier that evening the Republican Speaker of the House called The Pearl “the most exciting” economic development project he’s seen in North Carolina, and earlier in the week the Democratic mayor called it a “transformational investment in the future of our people.” And all the apolitical speakers in between tried to outdo each other’s superlatives.

Finally it was cocktail and dessert hour.

Woods, the CEO of Advocate Health and the visionary for the project, had already given the crowd a treat of a scoop: Johnson & Johnson had committed to establishing a presence at The Pearl, joining a long list of renowned medical technology companies. Now Woods figured he’d send everyone home with a song.

Woods wrote “Not Enuff Joy” back in his 20s, nearly four decades ago, before he was a hospital executive, and well before he was regarded by his Charlotte peers as one of the city’s most magnetic leaders. He’d seen a documentary about war in Africa and the lyrics spilled out: I look around the world, feeling so much shame/Not enuff joy, too much pain.

He resurrected the song in summer 2020, recording a music video for it during the pandemic to give people “a little reprieve and a reason to have a little fun,” as he writes in his book.

Now he was standing before a who’s who of leaders from the city and state and the wider medical world, singing those words again. Only this time it was at the grand opening of a campus he believes will discover breakthroughs that might help a stroke patient raise her arm again, or warn a heart attack victim before the attack.

In the company of doctors, the lyrics felt less like art or protest, and more like a scientific problem that they needed to solve.

“Not enuff joy,” Woods howled into the microphone. “Too much pain.”

A few weeks ago, former Bank of America CEO Hugh McColl told me The Pearl would be “the biggest rock in the pond you’ve ever seen.”

Tom Osha, the executive vice president of the development company for the project, called it “a beacon of possibility” and “a bridge between past and future,” and that it could become the world’s first “innovation constellation.”

Woods uses big comparisons to describe it, too, saying that he drew inspiration from the Italian Renaissance and “The Medici Effect,” which explores how innovation happens when people from across industries intersect. Woods’ team also uses metaphors, telling me that throughout the process of building The Pearl, Woods kept “throwing the buoy farther out into the water and telling us to swim to it.” Even if they couldn’t reach it, he figured, “they’d be in better shape.”

I spent most of last week talking to people about The Pearl, trying to understand it in a way that would help me demystify it. For transparency, Atrium is a founding donor for The Charlotte Optimist, but didn’t influence or review this story — though they did answer my countless ignorant questions. Somewhere in between the sweeping praise of The Pearl and the clinical news stories about it, I was trying to find what ties it together — what it actually is, and what it means for Charlotte.

I came up with my own, smaller metaphor: The Pearl is like a Smith Island Cake. What’s a Smith Island Cake? It’s an 8-to-14-layer yellow cake, with fudge in between each layer. Anyone can replicate the recipe, but only one place gives it meaning: Smith Island, a tiny, carless dot in the Chesapeake Bay with about 250 residents, where oystermen used to take the cakes out into the water on long days. What makes it a Smith Island Cake is the place, and the traditions of the place.

The Pearl is a multi-layered campus — where Wake Forest School of Medicine will train future doctors … where IRCAD will set up its North American headquarters to create the future of robotic surgery … where Siemens Healthineers and Medtronic and Boston Scientific and Stryker are installing their cutting-edge medical technology … where master developer Wexford Science & Technology will launch Connect Labs to give entrepreneurial life sciences companies lab and office spaces to help them grow … where Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools will send middle-school students to learn in a lab … where $400 million in private funding was raised … where an estimated 5,500 onsite jobs are expected to be created … where Wexford will soon build apartments and a hotel as part of Phase 2 … all under the banner of Advocate Health, formerly Atrium, formerly Carolinas HealthCare.

It’s a lot.

But what separates it from other “innovation districts” in the country, what makes it more than a couple of buildings where signage will surely change as companies are sold or merged, is that The Pearl name will stay. And what makes it The Pearl is the place, and the traditions of the place.

“We can hear the ancestors talking through the physical structure,” Arthur Griffin, who graduated from Second Ward High School in the former Brooklyn neighborhood, told me. The Pearl’s two towers now stand on what was the southeastern corner of Brooklyn. “I hope you can imagine life back then.”

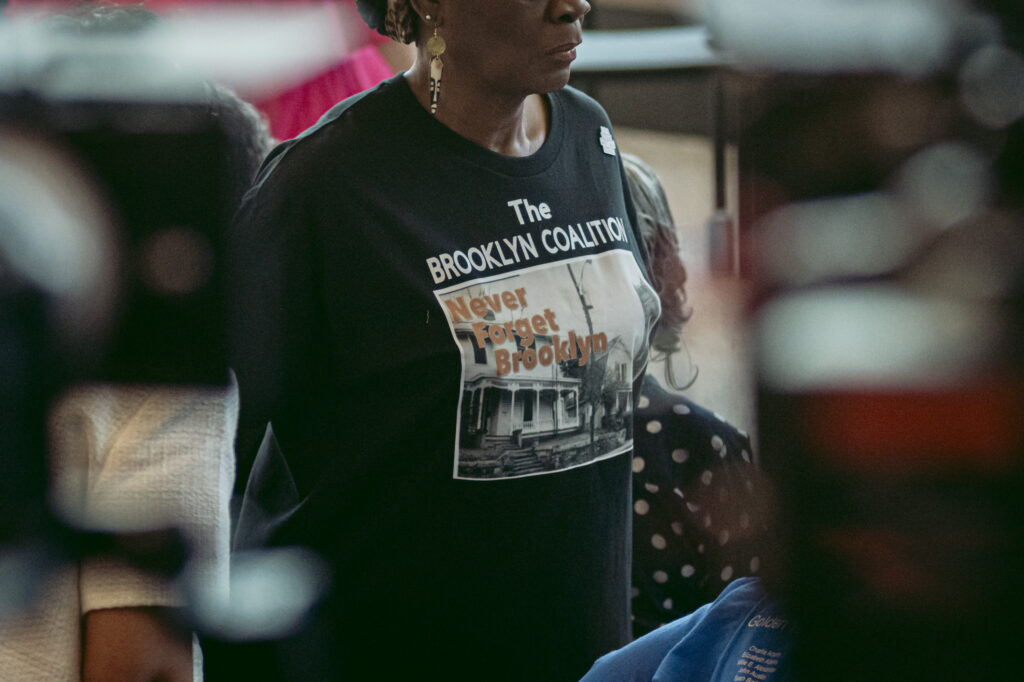

Back then, to him, means the 1950s and 1960s. And back then Brooklyn was the destination neighborhood for Black families in the city, with theaters, a grocery store, Second Ward High School, Myers Street elementary, and Pearl Street Park. In the 1960s and ‘70s, though, the city of Charlotte razed Brooklyn and other Black neighborhoods around the city core in the name of “urban renewal.” Or, as the people who grew up there remember it, “urban removal.”

Communities and families were blown and scattered like piles of leaves. Many moved out to the city’s west side, along Beatties Ford Road, believing city officials who told them they would return one day — after the “blight” was fixed.

It was just the first of many broken promises.

Over time former residents of the neighborhood contributed to countless conversations about developments here, with little follow-through from the entities that pulled them in. The latest frustration flared up again last week, when WFAE reported that the developer of Brooklyn Village withdrew its request for public money to construct 250 low-income housing units near what’s now the Mecklenburg Aquatic Center, about two blocks north of the Pearl. The developer, The Peebles Corporation, also wants an extension to bulldoze an empty building because of asbestos, WFAE reported. All this is happening nine years after the county entered into an agreement for Brooklyn Village. The future of the project is uncertain. But the mood is so sour around it now that commissioner Vilma Leake, who remembers going to church in Brooklyn, asked the developer last summer, “Will we ever finish it? Will I get to see it?” (Axios has a timeline.)

Faith is a fragile thing, and the former residents of Brooklyn have very little of it, for decades of reasons.

So when Atrium and Wake Forest announced plans for The Pearl in 2020, those former residents — along with those in the nearby Cherry neighborhood — voiced concerns about the project. They were particularly vocal when the county and city voted to support the project with up to $75 million in tax-increment grants. And as usual, they got calls to meet, this time with Atrium and Wexford officials. And as usual, the larger entities said they were there to listen.

“We asked them, ‘Are you like everybody else?’” Griffin told me.

This time, though, Atrium and Wexford kept communicating. They formed a committee to work with the various groups associated with the neighborhoods. Griffin serves as president of the Second Ward National Alumni board of directors, and says the conversations continued throughout the construction process.

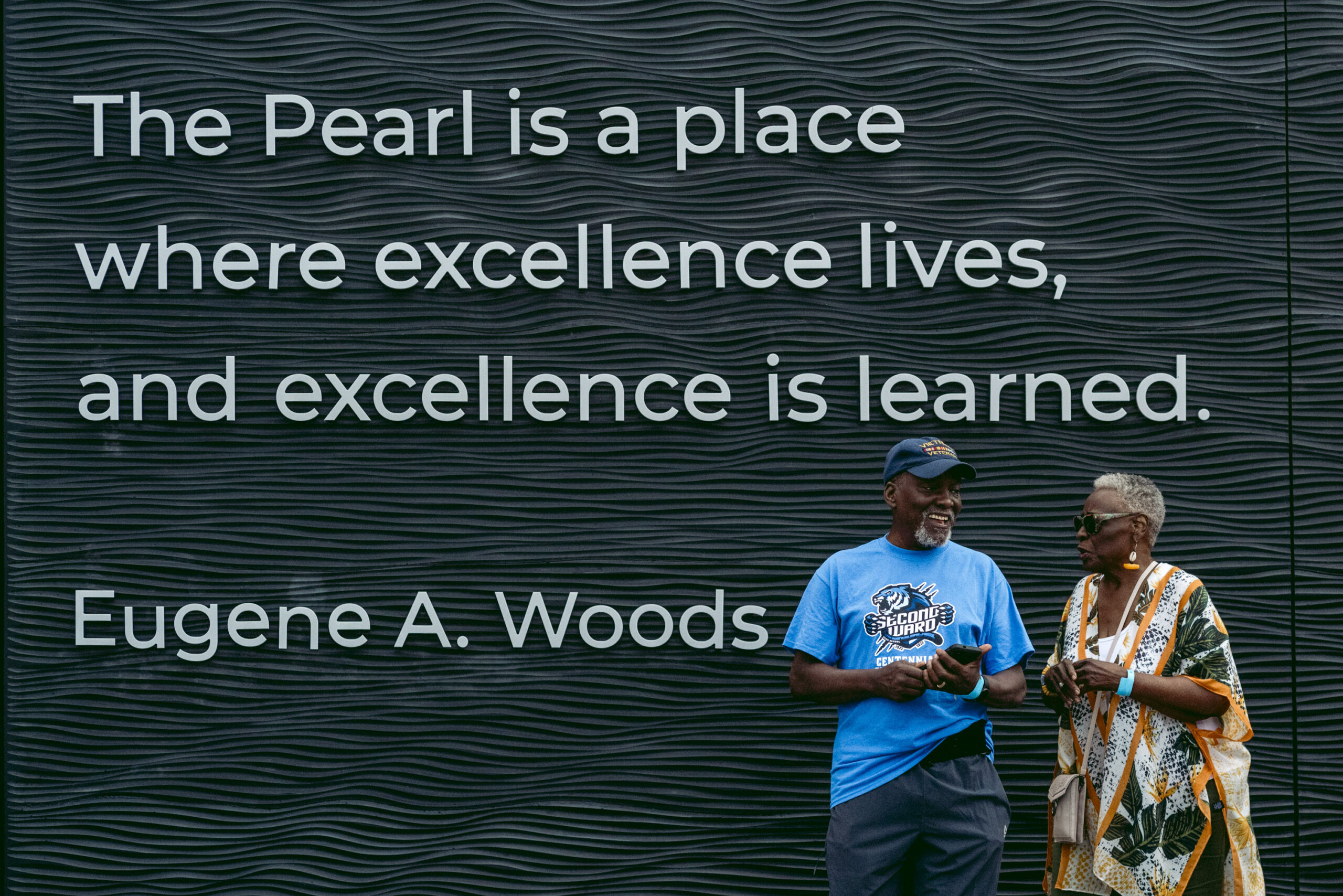

On Monday at the grand-opening ceremony, the front rows were reserved for people from those neighborhoods. Throughout The Pearl are reminders of Brooklyn. A “Purposeful Walk” winds around the buildings, with storytelling markers including quotes from the former residents and tales of the neighborhood’s most vibrant days.

The most noticeable tribute is the outdoor plaza between The Pearl’s main two buildings. It includes dozens of tables and chairs around a landscaped garden that scales two levels. Two concrete staircases begin on opposite ends of the plaza and meet at the top. They’re meant to resemble the old fire escape at the Myers Street School, where during the Jim Crow era children would sing hymns.

Back then, the fire escape was known as “Jacob’s Ladder.” The entire plaza at The Pearl now is called “Jacob’s Ladder.”

Names and storytelling walks won’t change history, the former Brooklyn neighbors told me last week. But they can preserve it. In a city that’s consistently criticized for tearing down its history in the name of progress, it’s notable that the most futuristic development is also rooted in permanent tributes to the past.

I asked Griffin why, in his view, this project was different.

“I have to credit Gene for following through,” Griffin said of Woods, who is also Black. “I think he felt the ancestors talking to him. Atrium came across Morehead Street. When he came across Morehead Street, I guess he realized how sacred that ground was.”

On Friday morning, the day after the celebrations, I sat at a table at the new version of “Jacob’s Ladder” to write, right in front of the waterfall feature with the quote from Woods: “The Pearl is a place where excellence lives, and where excellence is learned.” I was the only one there for an hour, but did see multiple people walk through the door of The Pearl with suitcases rolling behind them, as if they’d just arrived from the airport.

Most people, when they think of The Pearl, focus on the medical school, for good reason. Previous attempts to bring one to Charlotte led to frustrating results. In 2018, Atrium had an agreement with UNC Health Care, which would’ve included UNC Charlotte being the partner on a medical school. But that fell through, as Charlotte magazine documented.

But for economic development leaders like Tracy Dodson, the COO of the Charlotte Regional Business Alliance, the med school is only one reason for excitement. Dodson is looking forward to the visitors, bright and brilliant medical minds, who’ll now come to Charlotte for training. IRCAD’s presence at The Pearl is a coup for the city, said Dodson and other people I talked to.

The France-based surgical training and research center specializes in using modern technology for less-invasive surgeries. IRCAD chose The Pearl over other major health care powerhouses, including Cleveland Clinic, as the home of its North American headquarters.

IRCAD, scheduled to open here in September, was the main domino that led the other med tech companies, including Siemens, to join.

And because of Advocate Health’s size — it’s now the third-largest nonprofit hospital system in the country, stretching from Wisconsin to Georgia — the learnings and advancements that come out of The Pearl can be distributed throughout the network.

Advocate also oversees the Innovation Quarter in Winston-Salem, where Dr. Anthony Atala has pioneered regenerative medicine for two decades. Atala became famous worldwide in the late 2000s when news got out that he could grow human tissues to replace defective ones. Now he’s using 3D printers to create organs.

Advocate has rural facilities across its North Carolina network, connecting The Pearl and the Winston-Salem innovations with people in health care deserts. That’s part of what brought N.C. House Speaker Destin Hall, from Caldwell County, to the grand opening last week.

“It’s something that I think a lot of folks in our state haven’t caught on to yet, really what’s happening here,” Hall said on stage. “Anything that we can do as a state to continue to foster more doctors, more nurses, more medical providers, coming out, staying in North Carolina, going into some of those rural areas … I think in the long term has incredible benefit for the people of this state.”

I walked through the lab spaces with Collin Lane, a senior vice president for Advocate who’s been with the company since it was Carolinas HealthCare System. We visited the Medtronic Hugo, a one-of-a-kind robot that allows doctors to conduct surgeries from a seated station near the patient — surgeries that once would’ve required opening an entire torso, but now will only require them to go through a small opening.

A few floors up is one of Siemens’ photon-counting CTs, which can scan arteries for blockages in minutes, and deliver the same results as invasive catheters and dyes. Compared to typical CT scans, Lane says the photon-counting CT is “like going from tube TVs to today’s television.”

Why does that get an economic development leader like Tracy Dodson excited? Because doctors from all over the world will be flying in to train at IRCAD, to test out the equipment on the other floors, to interact with Wake Forest students, and to interact with CMS students. Connections, in other words.

Officials with The Pearl expect 8,000 physician visits per year. That consistent influx of brainpower was unimaginable seven years ago, when Amazon skipped Charlotte a finalist for its second headquarters, largely because the city didn’t have the research and development infrastructure.

Dodson wants them to have splendid visits. She’s thinking of ways to partner with hospitality providers to show off the city, in hopes that a few of those surgeons will move to Charlotte and set up their own practices here.

“I’ve spent 30 years in Charlotte,” Dodson told me. “I’ve worked on the first leg of light rail. I’ve worked on the Honeywell relocation, and Corridors of Opportunity. And the thing that gets me most excited, the thing I’m most proud of, is being a partner with The Pearl.”

One last story: Long before any of that, long before Woods pulled out the electric guitar, long before the speeches about how “transformative” all this will be, a little boy learned to carry a football on the same soil.

Jimmie Lee Kirkpatrick was faster and stronger than all the other kids at Pearl Street Park, the community hub for old Brooklyn. By the time he finished his junior year at the all-Black Second Ward High School in 1965, he was the finest football player in North Carolina.

Going into his senior season, though, Kirkpatrick was assigned to a new school, predominantly white Myers Park High. He could’ve tried to transfer back to Second Ward, but that summer — 60 years ago this month — he decided against it: “Negro Gridder Kirkpatrick to Enroll at Myers Park,” the Observer’s headline read.

The following fall Kirkpatrick ran through racism and everything else, leading Myers Park to its only undefeated season. But the all-star game between North Carolina and South Carolina, the Shrine Bowl, excluded him because of his skin color. That set off one of the most significant civil rights cases in Charlotte history. A judge ultimately gave a mixed ruling: The Shrine Bowl could ban Kirkpatrick that year, but the game must desegregate after that.

Three nights later, white supremacists unhappy with the ruling firebombed four houses in Charlotte, including the home of Kirkpatrick’s lawyer, Julius Chambers.

Kirkpatrick moved away from the mess, going north to Purdue to play football, then to California, and he settled in Oregon to become a teacher and administrator. He still lives there.

Why am I telling you all this, to wrap up a story about a medical school and research campus in Charlotte?

Because on Monday last week, I struck up a conversation with a man named Marvin Price. He was also a Second Ward High student, class of 1966. When I mentioned that I knew Kirkpatrick, not only did Price say he did, too, he said they were dear friends. And he pulled out his phone and called him.

“Hey, brother, what’s happening? Man, you need to be here,” Price said into his phone. “Boyyy, it’s a great day. Over here at The Pearl — Jimmie Lee, it’s unbelievable.”

Then Price handed me the phone.

Now, I’d heard leaders all around town say for years that The Pearl would be more than a med school, but I’m not sure I understood what they meant until this chance conversation at the opening led to a local civil rights legend’s voice in my ear again, from three time zones away.

“I wish I could be there,” Kirkpatrick said, voice as clear and deliberate as ever. “That’s where we grew up. That’s where we learned to play football. That’s where we learned to do everything.”

Maybe that’s what The Pearl is: a place of lessons, echoing from the past and calling from the future, in search of a little more joy and a little less pain in both directions.

Editor’s note: Atrium Health is a founding donor for The Charlotte Optimist, but did not influence or review this story.