This article is co-published with The Assembly.

Johnny Jennings has answered a great many questions about his recent challenges as Charlotte’s police chief, just not publicly. He can’t escape conversations about it. With his staff. With his wife and grown sons. With his mom, who is 84 years old and in Tennessee and calls whenever she sees a headline and asks, “Are they messing with you in Charlotte?”

And especially with his fellow police chiefs around the country. He’s part of a small group called the Major Cities Chiefs Association, where he swaps experiences, troubles, and wisdom.

“We’re all sitting in a chair with a bomb in it,” a close friend in the organization often says. “We just hope to get up before it goes off.”

Jennings is now getting up. He’ll retire from CMPD after 33 years of service on January 1, 2026, he told me Thursday. That date was signed as part of a widely speculated agreement with the city, which he also released to me.

In a wide-ranging, three-hour conversation, the embattled but still idealistic CMPD leader discussed the dispute over outer carrier vests that led to the agreement, his ups and downs as police chief since taking the job during the summer of unrest in 2020, his career and upbringing and family, and even a little fishing.

Notably, he never mentioned the name of former council member Tariq Bokhari, referring to him only by title when I asked specific questions about the year-long dispute over whether patrol officers should be allowed to wear outer carrier vests as part of their uniform.

We took a 45-minute break in the middle of our interview, during which he signed an amendment to his settlement agreement that granted him permission to release his personnel information. The original agreement, which he signed May 8 after council approved it in a closed session three days earlier, included a clause that said he and the city could not disclose it. He said he wanted to share it because “the benefits of releasing it outweigh protecting my information on a personal level.”

The total package amounts to $305,000, close to the figure that’s been reported, but it’s called a “separation agreement.” And it reads more like a severance package, breaking down like this (read the full agreement, and the amendment):

- $25,000 for costs he incurred in the dispute, including legal counsel.

- A 5 percent merit increase for 2025, retroactive to January 1, totaling $14,017.

- An additional 40 vacation days, valued at $45,284, to use at his discretion. If he doesn’t use them by January 1, he’ll be paid for them.

- A retention bonus of $45,699, paid in two installments, to stay through the end of the year while the city searches for his replacement.

- Severance of $175,000, to be paid in January 2026.

Our conversation capped a long month for a chief, and for Charlotte. He wants to focus on bigger things, he said, but he believed it was his duty, on behalf of other current and future department leaders, to stand up to a public pressure campaign mounted by a former council member. Charlotte has long operated under a strong-manager system of government, where the city manager reports to council but all department heads, including the chief, report to the manager.

“I was in a position to, let’s say, ‘We can’t keep doing this. We can’t,’” Jennings, 57, told me. “I felt like I had to look after the next chief, other city leaders, and it’s unfortunate that we’re even talking about this right now. But again, it’s my love for the city and my love for my peers within the city, in this department. And I just want to make sure that when you hire a leader to run a certain department within our city, then let them run the department.”

Bokhari, who left city council for a job in the Trump administration in the weeks before the city reached its separation agreement with Jennings, said he’s unable to comment.

My conversation with Jennings covered much of his life. It helped frame how he became a mild-mannered chief deeply concerned about the controversies swirling around him, but one who prefers quiet and old-school negotiations over a public back-and-forth in the media.

Jennings came up in a disciplined world, an Army brat and college football player who entered the police force before dial-up internet was widely used for communication. He’s leaving at a time when narratives and rules of order can shift with a single social post.

It’s in some ways a story as old as time: an exemplary public servant rises in the ranks, only to encounter frustration in dealing with the politics of the top job. The more public the disputes became, the more he stewed internally over how he spent 33 years in policing, only to end up in the chair with the bomb.

For those who haven’t been following over the past month or year, here’s a quick anatomy of the controversy.

When Jennings took the job in 2020, he continued a long-running department rule that restricted patrol officers from wearing outer vest carriers, or ballistic vests over the uniform, unless they had a medical exemption. The three previous police chiefs all had it in place, too. They believed the vests didn’t align with community-oriented policing philosophies, which attempt to bridge gaps between officers and the people they serve. Jennings had made “customer service” central to his administration, and he kept the uniform policy.

“That’s not the look that I want for our police department,” Jennings told me.

Bokhari, who represented south Charlotte until April, and the local Fraternal Order of Police believed all officers should have the option to wear them. This wasn’t a new position for them, either: Bokhari had been advocating for the vests for more than two years. He often cited research that showed the vests improved officer comfort, and conversations with officers who said they wanted the vests.

Jennings maintains that many officers didn’t want the vests, and that the loudest people don’t always represent the majority.

The standstill shifted in May 2024, in the aftermath of the deadliest day in local law enforcement history, when four officers were killed in east Charlotte. Three of them were wearing the outer vests, and Bokhari himself said the vests would not have changed the outcome of that day.

Still, Bokhari ramped up the pressure after that. He and Jennings discussed the vests multiple times over the next few weeks, and then Bokhari brought up the matter in a May 30, 2024 budget meeting. “I have come to the decision that this is the single-biggest impact to morale that we can make,” he said. “I want to be really clear, I don’t believe the role of council is to tell the chief how to run his department. … But there comes a time after two-and-a-half years when respect has been given and attempts have been made that other actions must be taken.”

He called it one of the most difficult positions of his life, taking a stand against the chief. And if Bokhari proved anything over his seven-plus years on council, it’s that when he believes he’s right, he uses every weapon he can to win.

“Burn the ships,” he’d told me of his political philosophy in 2021, citing the legend that Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés burned his ships after arriving in the New World in 1519. Cortés actually sank the ships, but you get the point.

Soon Bokhari launched an online petition. He also sent text messages to Jennings, first reported by WFAE, that got more intense throughout the summer. (Bokhari has said that he did all this in his capacity as a private citizen, not a council member.) In one July text, Bokhari said, “As your friend, I want you to know what happens next. I’ll be demanding your resignation starting Monday.” He added that he may not be successful but, “I will not stop and it will cripple your legacy you’ve worked so hard for.”

By August 2024, Jennings relented and changed his policy to allow patrol officers to wear the vests without a medical waiver. Bokhari thanked Jennings for doing so, publicly and privately.

But Jennings didn’t let it end there.

WFAE’s report on the texts didn’t come out until November, following a public records request. By then, Jennings had already retained legal counsel.

“It wasn’t about the text messages,” Jennings told me. “I keep hearing that, ‘Oh, you know, the chief had his feelings hurt over some text messages.’ I’m a former college football player. I’ve had my feelings hurt by coaches, but certainly not by words written down in text messages. It was more about what happened after. … Everybody focuses on the text messages, but not the other things.”

“What are the other things?” I asked.

“The push for me to be fired,” Jennings said. “The push for the city manager to be fired, the push for the petition for people to go online and sign for my termination or forcing the manager to fire me.”

To understand why the calls for his end were offensive to him, it’s worth going into his mind a little more and remembering something that kept coming up for him: He didn’t have to take the job in the first place. He mentioned multiple times in our conversation that he could’ve made more money if he’d just retired when he became eligible five years ago, or if he’d left for a private sector job.

Jennings came to Charlotte in the early 1990s in hopes of being a postal inspector.

He’d lived all over the world, as the youngest of six kids born into a military family. His father’s career took him to Germany and Wisconsin and eventually rural Tennessee. Johnny went to college at App State to play linebacker, and after graduation in 1990, he moved to Charlotte and pieced together a living working in group homes and as a fitness instructor at the Simmons YMCA.

He quickly learned how difficult it would be to get a job as a postal inspector. A friend recommended becoming a police officer. Jennings applied hesitantly, and was stunned to get a call to come in. He got his badge with the former Charlotte Police Department in 1992. A year later, CPD and the Mecklenburg County Police Department merged.

Jennings says proudly now that he’s the last remaining employee from CPD.

He worked patrol for a few years, then became a homicide detective. The first time his name appears in The Charlotte Observer was in September 1997, when he explained how a 17-year-old was murdered off of Tuckaseegee Road over $1.

He and his wife, Lisa, had three boys, including twins. He threw his life into them and work. They tried to eat dinner at the table as often as they could, he said. But he recalled how accustomed they became to him running to a scene at a moment’s notice. One night his phone rang, and his oldest son looked down at the ground in disappointment and sighed, “Dad’s gotta leave again.”

Jennings moved up to major and deputy chief, and along the way helped CMPD coordinate operations for major events like the 2012 Democratic National Convention.

In September 2013, a CMPD officer killed a 24-year-old unarmed Black man named Jonathan Ferrell in northeast Charlotte. Jennings was in the command center at CMPD when then-chief Rodney Monroe played the bodycam footage of the incident. He heard Monroe say the officer would be charged with voluntary manslaughter, immediately. And he remembered how, while people in the community praised Monroe and his investigators for acting swiftly, the chief lost the faith of many rank-and-file officers.

Three years later, he watched another police chief, Kerr Putney, handle a different police killing in a different way. In the days after Keith Lamont Scott was killed, protests both violent and nonviolent swelled in uptown, and Putney tried to emphasize that Scott had a gun, contrary to social media rumors. Putney’s blunt perspective and defense of his officers helped with police morale, but it brought significant criticism from community members, who filled city hall calling for his resignation.

Putney announced his retirement in 2019, but stayed on until July 1, 2020. In his last month, protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis erupted all over the country, including in Charlotte. Jennings was announced as Putney’s successor on May 20 that year, so he was shadowing Putney for much of the 2020 protests.

What hasn’t been widely reported locally is this: Jennings had another job offer at the time, to become police chief in Greenville, South Carolina. He also had enough years of service, plus leave time, in Charlotte to retire. He could’ve collected his pension in Charlotte and taken a top chief job in another city. But he chose to take the CMPD job instead.

He uses the analogy of sports to explain: “Most athletes would love to retire with the same team that they came in on, and that’s difficult to do. So, you know, there are very few of us [who] get an opportunity to be a chief in your originating department, and it was hard to pass that up.”

After Putney announced his retirement in 2019, I asked Bokhari, then a city council member and a well-known advocate for police, what he hoped the next chief would bring.

“The balance between supporting your officers, giving your men and women air cover [and] at the same time if you [an officer] do something wrong, truly wrong, you’re going to be held accountable.”

Jennings agreed with that, then and now. He said he spent most of his first days in 2020 trying to show that he could find that balance, in the wake of the George Floyd protests.

“I’ve tried to have that blend,” he said. “How do we regain the community support? And then also, how do we keep morale and keep our officers doing the job that they’re here to do?”

By September 2020, he announced that the department was in compliance with the “8 Can’t Wait” policy platform, outlining progressive reforms in policing. He also expanded the office of employee wellness within the department, in hopes of improving morale and mental health for officers—and to help with recruitment.

That last part was much-needed, he said. CMPD endured a wave of departures around 2020, as the officers who joined in an early 1990s hiring wave hit retirement age, and others gave up the job amid the public scrutiny. The total vacancies hit about 300 during Jennings’ tenure, but he told me it’ll soon be down to about 100.

The results in the city have been mixed, at least in terms of homicides. In 2020, his first year as chief, Charlotte saw 118 murders, its second-deadliest year on record. That number dipped to 95 in 2023 before spiking back up to 110 last year.

Youth violence still plagues the city. And Jennings said the victims and assailants are getting younger. “Now we can have examples of 14- to 15-year-olds, and that’s what scares me more than anything,” he said.

Still, he’s optimistic.

“This agency … has the most respect across the entire country, and I don’t think most of our people even know how respected our agency is,” he told me. “I’m proud to be a part of that. We have been a model across the entire country for many things that we do.”

In April 2024, Jennings was planning to announce his retirement, but hadn’t settled on a date.

But on April 29, he was in a meeting when he got a text message that told him there was an incident on Galway Drive that needed his attention. He got in the car and started making phone calls. In the first one, he heard that an officer was shot. In another call, he heard that they didn’t know whether officers were shooting or if they’d been shot. So he went to the scene. When he arrived, the area was blocked off, and one officer told him to stop.

“The officer’s telling the chief of police, ‘You can’t go somewhere,’” Jennings recalled.

Four officers, including one CMPD officer, were killed while trying to serve a warrant. Jennings knew immediately that the event would affect his department for years. In the weeks that followed, he sent a wellness team of officers to Dallas to gather lessons from when five officers were killed in 2016, and to ask the question: “What do we have to worry about in four or five, six years?”

He also told his wife he wanted to delay his retirement, to see the city through it.

“Every day, every night, was constantly a race in your mind,” Jennings said. “My focus had to be here within CMPD. I was taking care of our people, and had made sure they had resources to get through it, because if we couldn’t take care of them, they couldn’t take care of our community.”

Within a month, though, he had other issues.

Charlotte’s city government now finds itself swatting at controversies. Last week, city council member Tiawana Brown was indicted on charges of fraud related to COVID relief funds. Also, state auditor Dave Boliek announced he would open an investigation into the city’s closed-door settlement with Jennings. And the Fraternal Order of Police will soon take up a “no confidence” vote against the chief.

Jennings says he hopes releasing the agreement himself will help with public trust. He also wants to be clear: He’s retiring because it’s time to retire, not because of all this.

He could’ve retired in 2020, but stayed on. He planned to retire in 2024, and stayed on. He already has his next career lined up, he said, and planned to step into it earlier this year, but will stay on for seven more months to assist with the transition, despite the lingering controversy and reputational damage.

“I’m not worried about myself,” he said. “Where I become enraged is the effects that it has on my wife, the effects it has on my kids. … That, to me, is the effect that I don’t know people realize. Or if they realize it, then they don’t care.”

This was toward the end of our conversation. By then it had become apparent that Jennings hasn’t spent the past year in a conflict over tactical vests, or transparency, or interviews. He was facing down a new breed of confrontation and policy-making—a theater of online comments and optimized headlines—that ran counter to his nature. He was ill-suited, for better or worse, to tangle with his media-savvy opponents online.

“I’ve never treated people like that,” Jennings said. “And to publicly try to defame someone, through social media, through the media, through any of that—I just think there’s too much of that that goes on in our world nowadays, and it’s a shame.”

When I asked him what he wanted his legacy to be, he brought up the customer service initiative CMPD installed in 2021, and how officers now strive to be “the best part of someone’s worst day,” and that he hopes his legacy is that “we were a nicer department to the people that we came in contact with, externally and internally, and we recognize those officers that were day makers.”

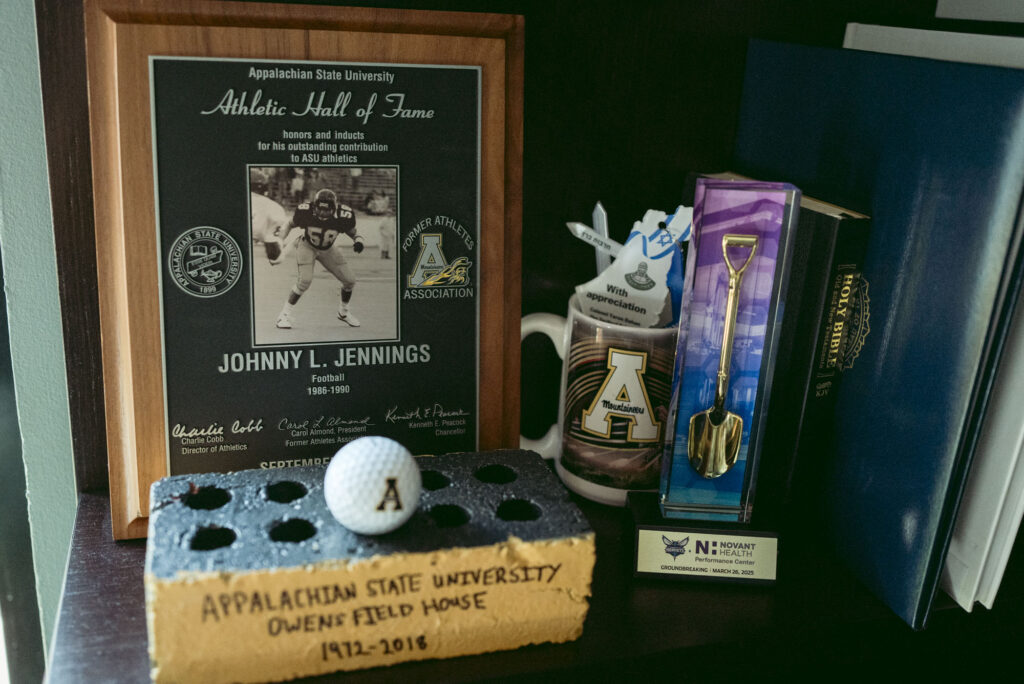

He knows his answers won’t quell his critics, but he seemed lighter after our interview. During our last 15 or so minutes in his office, he talked mostly about fishing and football and having dinner recently with two of his mentors, his former coaches at Appalachian State, Sparky Woods and Jerry Moore.

He romanticizes those old days when he was a linebacker and team captain, putting together a career that landed him in the App State Hall of Fame.

With time, the wins and losses mix like watercolors.

“I go back to my football career, and I talk about, ‘Oh how great it was, how much fun it was.’ I forget about the winter workouts, the spring practices, the weight room and how difficult and crazy it was,” Jennings said.

“I hope it is here that … five years from now, I will be looking back [on the police chief job] and saying, ‘Wow, that was awesome.’”