Originally published on February 15, 2025. Updated on February 16.

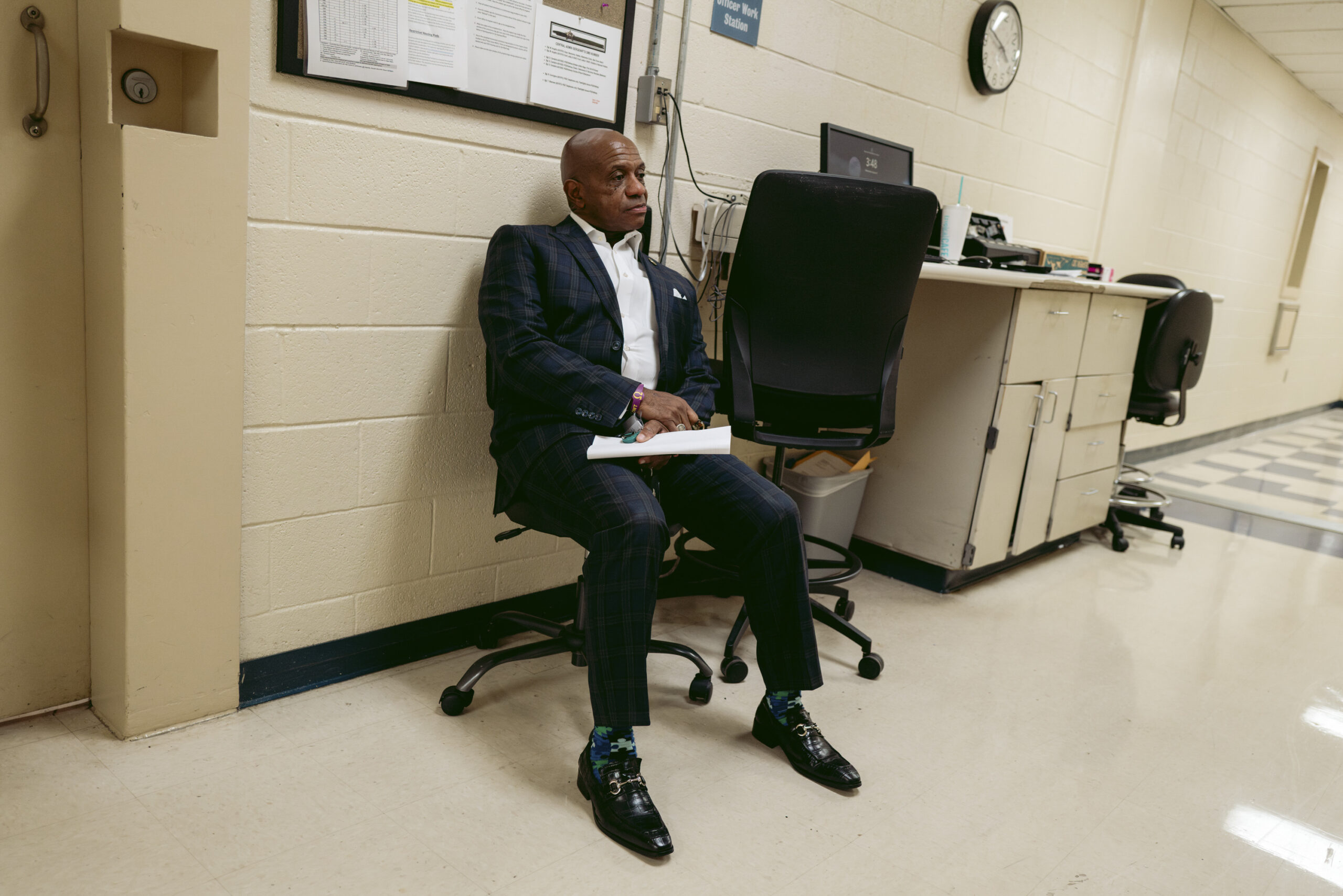

As he packed to leave for Raleigh last weekend, ahead of his now-notorious appearance before a state house committee on Monday morning, Garry McFadden spoke with his wife.

“For the first time in 37 years of our marriage,” the embattled Mecklenburg County sheriff told me, “she looked me in the eyes and said, ‘Why are you still doing this?’”

“Because I’m not done yet,” the 66-year-old responded. “God gave me an assignment.”

Cathy McFadden is hardly the only one asking that question now, after legislators scrutinized McFadden during a 2.5-hour, made-for-reality-TV-series hearing. The internet deals in clips not episodes, though, and the 90 seconds that made McFadden most infamous came when House Rep. Allen Chesser asked a basic civics question to name the three branches of government, and McFadden couldn’t do so.

Fox News star Sean Hannity shared the moment with his more than 7 million followers on X, and Chesser and other legislators have made national media appearances in the hearing’s wake.

(The trending tornado overshadowed a key point, as Western Carolina University professor Chris Cooper pointed out to me after this story initially published. Turns out, when Chesser asked McFadden which branch of government he “operated under,” and McFadden replied, “Mecklenburg County,” the sheriff was correct. “North Carolina sheriffs don’t fit neatly into the three-branch framework,” Cooper wrote in his Anatomy of a Purple State newsletter Monday morning. The North Carolina constitution establishes the sheriff as an agent of local government.)

Still, even under the most generous lens — one where, perhaps, most of us can admit we don’t know how we’d handle taking a high school civics test in front of an audience of powerful lawmakers — the hearing and fallout were hard to watch, especially for us Mecklenburg County residents.

Rep. Brenden Jones, the House Oversight Committee chair, punctuated the hearing with the final words: “It’s time to look in the mirror, sheriff. That’s where the mistake is.”

I waited a day to call McFadden to hear his assessment. He was quick to fire back at the legislators, and was frustrated that the single clip was all anyone could talk about. He said of the viral moment: “It’s Sean Combs with baby oil. Everybody’s going to post it. But what have we accomplished? Nothing.” I told him I was looking for a more level evaluation, not soundbites, and suggested we talk later in the week, after he’d had more time. He agreed.

In my 13 years in Charlotte, I’ve seen McFadden hand out countless turkeys at Thanksgiving, seen him help barbers use their positions to deter crime, and seen him give Bojangles gift cards he’d purchased himself to kids.

But this wasn’t Thanksgiving, and McFadden wasn’t facing barbers or kids. He was facing legislators. He’s already under a heap of controversies, many of which we outlined in our Labor Day feature on him: from claims from former employees that he runs a “dictatorship,” to an alarming number of deaths in the jail under his tenure, to his use of racial slurs in a recording. His performance at the hearing was, at best, entertaining — and at worst, a showcase of his inability to see his own tragic flaws.

The hearing, I should say, was supposed to be an examination of public safety in Charlotte in the wake of Iryna Zarutska’s murder on a light-rail train last year. McFadden was part of a group of people from the county to attend and be questioned. They included: District Attorney Spencer Merriweather, City Manager Marcus Jones, CMPD Chief Estella Patterson, and Mayor Vi Lyles.

All of the others left with reputations either fully intact or enhanced. Merriweather, in particular, drew praise from lawmakers and observers from both sides of the aisle for his steady answers and ideas for improving public safety here. In my view, Merriweather’s most remarkable performance came after he was questioned, when he sat next to McFadden for two-and-a-half hours and never let his expression change, not even when McFadden said this:

“I am the elephant in the room,” McFadden said. “But I’m the proud elephant in the room. And I will always be the proud elephant in the room, and the state.”

Why does any of this matter, beyond the spectacle?

The biggest reason for any of you registered to vote in Mecklenburg County: McFadden’s future as sheriff will be decided by Democratic and unaffiliated voters in the March 3 primary.

The title is more than ceremonial. The future sheriff will be critical to determining whether the county will reopen the juvenile detention center in north Mecklenburg County, so that young people arrested here don’t have to be sent to facilities elsewhere. McFadden shut down the juvenile detention center a few years ago, citing staffing shortages.

He says the sheriff’s office already has about 100 vacancies, and that staff is overworked. Reopening the juvenile detention center would require hiring an additional 98 people.

The issue has become central to the campaign. Three Democrats oppose McFadden. Former Chief Deputy Sheriff Rodney Collins and CMPD Sgt. Ricky Robbins have extensive resumes and have rallied impressive support. Antwain Nance worked for two years as a detention center officer and argues inexperience could be a strength.

There is no Republican candidate, so whoever wins the primary will be the next sheriff.

All four candidates were given equal platform at a Sarah Stevenson Tuesday Forum in January, and many anti-McFadden voters are deciding between Collins and Robbins. “I’d be happy with either of them,” one longtime westside resident told me afterward. The Charlotte Observer’s editorial board recently endorsed Robbins, as did the local Fraternal Order of Police. But McFadden earned the coveted Black Political Caucus endorsement.

The three challengers all suggested that McFadden’s leadership issues and regular controversies are the source of the staffing troubles. And all three said that a sheriff’s office with them in charge would have better success recruiting.

I asked McFadden directly in our follow-up phone call on Friday: “Do you think if you stepped away, recruiting would get better in the sheriff’s office?”

“No, no, no,” he said, as if going down the list of opponents.

Then he asked me what my favorite baseball team was. I said the Orioles. He asked if I had a choice to play for them or any other team in Major League Baseball, which would I choose? Of course, he jumped in, I would choose the team I thought highly of.

Never mind that I’m 46 and my arm hurts after playing catch with my kid, his point was this: People talented enough to choose their workplace go to organizations they admire. He believes “negative” portrayals of him in settings like Monday’s, or in the media, make it more difficult for him to recruit. It’s why he fumbled through a response in the hearing about why people should speak well of law enforcement.

“Where are we going to get 98 people from?” he said, before turning to critics. “Here’s what we don’t understand, Mike: You have said this is the worst place to work. You have said this is poor leadership. You have said how bad this is. Even when my staff walks into a grocery store in their uniform or stops and gets gas, what do you think somebody asks them: ‘How’s it working for the sheriff? Is the sheriff really all that crazy? Oh, how do you feel? Why do you work there?’”

I asked him whether, given the staffing issues, he supported the new first responder training facility being built near Matthews. Central Piedmont Community College is leading the $118 million project, on 23 acres of land donated by Hendrick Automotive, to help train people to work for the fire and police departments, and as medics. The center faces modest opposition from activists who liken it to the controversial “Cop City” project in Atlanta, which began operations last year.

McFadden says he does support it, if it does what it promises to do.

“I don’t have space for training,” he said. “Yeah, we could benefit from it — we could all benefit from it — but will we get the benefits?”

To go back to the hearing for a moment. The intent was, in theory, to get to the bottom of the failures of Charlotte leaders that led to the murder of 23-year-old Zarutska on the light rail last August.

WFAE’s Steve Harrison wrote in his “Inside Politics” newsletter on Friday that the committee could have asked tougher questions of the other panelists, but didn’t. At one point, Mayor Lyles even had a fun discussion with the legislators about Charlotte’s recent pro sports success.

McFadden surely believes he was singled out. “They dodged a bullet, and I helped them dodge a bullet,” he told me. And later: “Who did we embarrass the most? Iryna. This was nothing but, ‘Let’s get Sheriff McFadden to hang him.’”

Several times during their questioning of McFadden, legislators praised the 99 other sheriffs who are doing their job, making McFadden the only one of North Carolina’s 100 sheriffs who is not.

Here’s the thing about that: North Carolina’s sheriffs have a long and recent history of skating up to the edge of abusing power, or flat-out breaking the law, all while enhancing their fame and notoriety. In fact, as recently as 2010, people convicted of felonies could still serve as sheriff. The state created a constitutional amendment that year because six felons were running for the position around the state, as pal Jeremy Markovich noted in his NC Rabbit Hole newsletter.

One of them was former Davidson County Sheriff Gerald Hege, who tried to run for the office twice after pleading guilty to obstruction of justice in 2004. Like McFadden, Hege starred in his own reality show at one point, in which he painted the jail walls pink. Hege also drove a famous Spider Car. But here’s how I remember Hege: I was an intern at theHigh Point Enterprise in the summer of 2000 when Hege called local newsrooms while he was involved in a high-speed chase — yes, during the chase — to make sure we covered it.

It’s not just sheriffs of days gone by, either.

Just three years ago, the sheriff in Columbus County — in Oversight Committee chair Jones’s home district — resigned twice in a span of 10 weeks after making racist remarks. And on Feb. 6 of this year — just three days before the hearing — Cherokee County Sheriff Dustin Smith announced he’s stepping down because of a series of scandals, including the shooting of an unarmed man in December 2022, and the fatal shooting of a detention center officer by an inmate who’d escaped from the jail there. Smith’s announcement came days after the district attorney there asked Smith to step down in a letter, which you can read in this WLOS story.

And McFadden isn’t the only one saying that new laws have led to overcrowding in jails. Alamance Sheriff Terry Johnson, no stranger to lawsuits and controversies himself, announced in November that his office could no longer house people detained by ICE due to “operational issues” like bed space, the office said in a release.

We tend to see people as outliers in a moment. But it doesn’t even take a long memory to remember 2007 and Nick Mackey, the Mecklenburg Sheriff-elect who resigned before even taking office.

Point being, not only is McFadden not North Carolina’s most audacious sheriff this century, he’s not alone in his staffing and space issues, he’s not alone in local history, and he’s not even the most troubled sheriff in the state this month.

When we talked on Friday, McFadden was a little more reflective than on Tuesday.

But he still didn’t find any flaws in the mirror. He held the same lines of thought: that recruiting would be easier if people stopped throwing arrows at him, that the deaths in the jail were a result of conditions beyond his control, that he’s handled a series of thorny issues (immigration, COVID, the 2020 George Floyd protests, other national political tensions) better than anyone else could have, and that Black sheriffs face more scrutiny than others.

Agree with him or not, he sees himself as different from the other officials who were called to Raleigh, despite the fact that they, too, are all Black. Merriweather grew up in the Deep South of Alabama with a mother who went to a school that still advertised Klan meetings on the walls. Lyles came from segregated Columbia, South Carolina, and broke barriers when she enrolled at Queens College only a year after it integrated.

Still McFadden says people make an example out of him because he’s not “nice,” like they are. It’s central to his worldview that being interrogated and condemned by a committee of legislators is an extension of what his ancestors endured.

Frankly, Garry McFadden’s views on Garry McFadden were no different Friday than they were Tuesday, and they’re no different from what they were back in August when I interviewed him over two days, and they’re hardly different from when he was first elected sheriff in 2018.

This is who he is. And that may be enough to propel him to another term. He’s built lots of support over nearly four decades as a law-enforcement officer here, solving hundreds of murder cases as a CMPD detective before his retirement from that department. The BPC endorsement still carries weight. His relationships with Latino leaders remain strong and are maybe even stronger, after this fall’s CBP raids. And the fact that anti-McFadden voters have multiple options only helps him in an election.

The dominant piece of a sheriff’s job, though, is to run the jail and ensure the safety of the 1,800 or so people detained there. That requires a robust, equipped staff. The number of people in jail continues to rise, and if McFadden isn’t the person to solve the staffing situation, Charlotte won’t be safer. He told me he has a meeting Monday with organizations that want it open, and he will ask for their help.

The local FOP and area Republicans have asked him to resign. The Oversight Committee was so displeased with his answers that they sent a series of requests for records. McFadden told me Friday he’s working on fulfilling the requests.

Regardless where the hearings go or how an SBI investigation into McFadden lands, voting in the primary election has already started. The sheriff’s race is at the bottom of most Mecklenburg ballots, and I suspect it’ll be the one many people linger over longest.

McFadden, though, says he’s prepared for whatever’s next.

He told me he spent some time last week looking up the resort he and Cathy have grown to love in Cancun. They go twice a year.

“People ask me, ‘How are you?’ I’m fine. Why?” he said. “Because I have given you everything that I can possibly give you, and if you don’t recognize it, why am I still beating my head and trying to make you recognize it?

“You vote for me, you vote for me. You don’t, I’ll be in Cancun four times instead of two.”

Editor’s note: We updated this story to include Chris Cooper’s research into the North Carolina constitution, which show that North Carolina sheriffs are not a part of the executive branch, but instead are agents of local government. Subscribe to Cooper’s newsletter here.